[iad]

cogito ergo sum

http://thegood007.tistory.com/entry/cogito-ergo-sum

http://thegood007.tistory.com/1180

03fl--cogito-ergo-sum.txt

◈Lab value 불기2559/03/24/화/07:57 |

나는 생각한다 고로 존재한다.

|

|

문서정보

ori

http://thegood007.tistory.com/1180#5881 03fl--cogito-ergo-sum.txt ☞◆pzbj5881 |

>>>

>>>

코기토 에르고 숨

코기토 에르고 숨(라틴어: Cogito, ergo sum,

해석: 나는 생각한다. 그러므로 나는 존재한다.)은

데카르트가

철학의 출발점이 되는 제1 원리를 말한다.

사실 데카르트는 이 명제를 프랑스어로 말했으나

( "Je pense, donc je suis")

《신의 도시(De Civitate Dei)》에서 동일한 표현을 사용했기 때문에

데카르트 철학이 상징하는

중세와의 단절을 강조하기 위하여

라틴어 표현이 훨씬 더 널리 쓰인다.

《성찰》에서 데카르트가 많이 사용한 명제이기도 하다.

개요[편집]

“cogito ergo sum”라는 표현 자체는

데카르트의 《성찰》에서는 직접 언급되지는 않지만

‘코기토’라는 표현은

이 경구를 가리키기 위해 쓰였다.

데카르트는 그의 초기 저작에 속하는 방법서설에서

이 구 자체를 사용했는데,

후에 그는 그가 추론하려 해 왔던 내포된 의미가 잘못된 방향을 가리키고 있어왔다고 생각했고,

그에 따라 그는 “cogito ergo sum”이라는 표현을

“나는 존재한다(곧 제1의 확실한 사실)”로 바꾸었다.

내가 존재한다는 제1의 확실한 사실과

코기토라는 표현을 분리하기 위해서이기도 했다.

두 번째 성찰의 시작부분에서

그는 그가 부정의 극한 지점이라고 일컫는 지점에 이르게 된다

(그의 논증은 우리를 속이는 신의 존재로부터 시작한다).

데카르트는 그 부정 속에서 남아있는 것이 존재하는지를 보기 위해

그의 믿음까지도 실험(사고실험) 속에 넣어본다.

그의 존재 속 그의 믿음 속에서

그는 이것을 발견한다:

스스로의 존재를 부정하는 것은 불가능하다.

심지어 우리를 속이는 신이나

그의 근거없는 믿음을 멈추게 하기 위해 쓰인 도구인 악마가 존재한다고 해도

그의 존재에 대한 믿음은 여전히 근거있는 것이다.

그가 속아넘어가기 위해 존재하는 것에 불과하다고 하더라도 말이다.

“그러나 나는 이 세계 안에 어떠한 것도 없다고,

하늘도, 대지도, 마음도, 신체도 없다고

나를 확신하게 만들 수 있다.

그렇다면 나 역시도 존재할 수 없는가?

그렇지 않다:

만일 내가 나의 확실한 존재를 나에게 확신시켰다고 치자.

그래도 나를 속이는 절대 권력과

일부러 그리고 지속적으로 나를 속이는 자는

존재한다.

그러한 경우에도

내가 존재한다는 사실은

여전히 속일 수 없는 것이다.

만일 속이는 자가

나를 계속 속이고

또 그가 가능한 만큼 나를 계속 속이게 한다고 해도,

내가 어떤 존재라는 것을 내가 생각한다면

나는 존재하지 않는다는 결론을

그는 결코 도출해 낼 수가 없다.

따라서 모든 것들 철저히 고려해 봤을 때,

나는 다음 명제와 같은 결론을 내려야만 한다:

“나는 존재하며, 또한 나는 존재한다.”

이 명제는 반드시 참이다.

나에 의해서건,

내 마음 속의 속이는 자에 의해서 말해지건 말이다.

중요한 주석이 두 개 필요하다.

- 1) 여기서 그는 오직 제1 인간의 시점에서 본

- “내가 소유한” 존재의 확실성을 선언했을 뿐이다.

- 그는 다른 마음의 존재를 증명해내지 못했다.

- 이는 별도로 우리 각각에 의하여 우리 자신을 위해 사유되어야 하며,

- 《성찰》에서 데카르트는

- 윤리학에 대해 코기토와는 별개의 논거를 추가하여 설명을 시도한다.

- 2) 그는 결코 그의 존재의 필요성에 대해 말하지 않았다.

- 그는 이것을 말했을 뿐이다:

- “만일 그가 생각한다면” 그가 반드시 존재한다는 것만을.

데카르트는 더 상위의 지식을 쌓기 위한 기초인 코기토

즉 제1의 확실성을 앞의 인용에서 사용하지 않았다.

그보다는 코기토는 그의 믿음을 다시 세우기 위한

그의 사유 대상으로 정립된 굳건한 기반으로 쓰인다.

아르키메데스는

단 하나의 굳건하고 움직일 수 없는 점을

지구 전체를 움직이기 위해 늘 요구했다;

그처럼 나 역시 하나의 위대한 것을 실현키 위한 희망을 가지고 있다.

만일 내가 오직 한 가지를,

그것도 물질적이지 않은(slight) 것을 찾아내야만 한다면

그 하나의 위대한 것은

바로 확실하고 흔들 수 없는 것이 될 것이다.

흔한 오류들[편집]

철학자가 아닌 몇몇 사람들이

코기토를 비판하기 위해 했던 시도는 다음과 같다.

“나는 생각한다, 따라서 나는 존재한다”는 이 명제는

이렇게 이의 명제가 된다.

“나는 생각하지 않는다, 따라서 나는 존재하지 않는다”

그들은

바위는 생각하지 않으나 존재한다는 예를 통해

데카르트의 명제를 반박해 냈다고 생각한다.

그러나

이것은 명제들의 관계를 이해하지 못한

논리적 오류에 불과하다.

모두스 톨렌스 즉 대우에 의한 옳은 결과는

“나는 존재하지 않는다,

그러므로 나는 생각하지 않는다”이다.

이런 오류와 이것의 빈발성은

다음과 같은 조크에서 잘 그려지고 있다.

하루는 데카르트가 바에 앉아서 술을 마시고 있었다.

바텐더가 다가와서는 이렇게 물었다.

“당신, 다른 남자 좋아한 적 있소?”

“그런 생각 한 적 없소.”

데카르트가 이렇게 답하자,

그는 동성애자의 논리에 의해

사라져버렸다!

코기토에 대한 비판[편집]

코기토에 대한 많은 비판이 지금까지 제기되어왔다.

맨 처음 살펴볼 것은 바로

“나는 생각한다”와 “나는 존재한다”라는

두 명제의 본성을 통한 비판이다.

이것은

삼단 논증의 제1명제와 결론명제에 해당하는 것으로,

이와 같은 제2명제를 도출해 낼 수 있다.

“사고를 소유한 어떠한 것이라도 존재한다”

이 명제는 스스로 증명될 수 있는 것이며

따라서 부정의 방법에 의해 부정될 수 있는 성질의 것이 아니다.

이는

이러한 형태의 명제는 모두 참이기 때문이다:

“F를 소유한 것은 어떠한 것이든 존재한다.”

이러한 방식을 사용하는 비판자들은

부정의 방법이 통하지 않는 명제가

추가적으로 더 존재한다는 점에

주목하는 것 같다.

그러나 부정의 방법 안에서

사고의 소유자는

의심할 바 없이 그 방법을 사용하는 성찰자일 수밖엔 없다.

헌데 데카르트는

이런 식으로 방어하려 들지 않는 것 같다:

우리가 이미 보았듯

그는 실제로 요구된 나머지 명제가 존재한다는 것을

인정하는 것에 의해서만

비판에 반응할 것이다.

그러나 코기토를 부정하는 것 역시

삼단 논법으로 이뤄진 것이다.

-->

아마도 좀 더 적절한 논쟁은

데카르트가 ‘나’라고 지칭한 것이 정당화될 수 있는가에

초점이 맞춰진 것이다.

버나드 윌리엄 의 논문

<데카르트, 순수 학을 위한 기획>은

이 문제의 역사와 그에 대한 평가를 다루고 있다.

그 주된 목적은

게오르크 리히텐베르크에 의한 평가대로

사고하는 실재를 뒷받침하는 것이라기보단

데카르트는

다만 이렇게 말했어야 했다는 것에 있다:

“어떠한 사고가 행해지고 있다.”

즉 코기토의 힘이 어떠하든지

데카르트는 거기서부터 너무 많은 것을 뽑아냈다는 것이다:

사유하는 것의 존재, 즉 “나”로 지칭되는 것을

코기토가 정당화하기에는 무리가 있다.

버나드 윌리엄의 비판[편집]

윌리엄은

신중하고도 철저하게

이 주제에 대하여 사고실험을 행한다.

그는 먼저

사고하는 것의 존재를 느끼는 것은

다른 어떤 것과의 상호작용(relativising) 없이는 불가능하다고 논증한다.

이 어떤 것은

사유하는 자, 곧 나를 요구하지 않는 것처럼 보인다.

그러나 윌리엄은

각각의 가능성을 모두 타진해보고,

어떠한 작업을 수행하는 주체 없이는

그는

결국 데카르트는

그의 정식을 정당화해냈다고 결론짓는다.

코기토에 대한 두 가지 논증이 모두 실패하는 동안,

다른 방안이 윌리엄에 의해 나타나게 된다.

그는 우리가 사유에 대해 말할 때나

우리가 “나는 생각한다”고 말할 때

우리는 문법적으로 3인칭의 관점에서

우리를 바라보게 된다는 점을 지적한다;

실제로 앞의 경우에는 사유한다는 것이 목적어로서 쓰였고,

뒤의 경우에는 생각하는 자가 목적어로 취급된다.

그런데 우리는 어떠한 자기 반성 또는 우리의 의식의 경험을 통해서도

삼인칭 사실이 실재한다는 결론으로 나아갈 수 없다.

그것을 확인하는 데 사유는 필연적으로 불충분하며,

데카르트가 인정했던 것처럼

그가 가진 의식이 홀로 존재한다는 사실 이외에는

다른 어떠한 증거도 추출될 수 없다.

이 문서는 2014년 9월 29일 (월) 15:36에 마지막으로 바뀌었습니다.

>>>

>>>

>>>

Cogito ergo sum

Cogito ergo sum[a] (/ˈkoʊɡɨtoʊ ˈɜrɡoʊ ˈsʊm/, also /ˈkɒɡɨtoʊ/, /ˈsʌm/; Classical Latin: [ˈkoːɡitoː ˈɛrɡoː ˈsʊm], "I think, therefore I am", or better "I am thinking, therefore I exist") is a philosophical proposition by René Descartes. The simple meaning of the Latin phrase is that thinking about one’s existence proves—in and of itself—that an "I" exists to do the thinking; or, as Descartes explains, "[W]e cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt … ."

This proposition became a fundamental element of Western philosophy, as it was perceived to form a foundation for all knowledge. While other knowledge could be a figment of imagination, deception or mistake, the very act of doubting one's own existence arguably serves as proof of the reality of one's own existence, or at least of one's thought.

Descartes' original phrase, je pense, donc je suis (French pronunciation: [ʒə pɑ̃s dɔ̃k ʒə sɥi]), appeared in hisDiscourse on the Method (1637), which was written in French rather than Latin to reach a wider audience in his country than scholars.[1] He used the Latin cogito ergo sum in the later Principles of Philosophy (1644).

The argument is popularly known in the English speaking world as "the cogito ergo sum argument" or, more briefly, as "the cogito".

Contents

[hide]In Descartes' writings[edit]

Descartes first wrote the phrase in French in his 1637 Discours De la Méthode. He referred to it in Latin without explicitly stating the familiar form of the phrase in his 1641 Meditationes de Prima Philosophia. The earliest written record of the phrase in Latin is in his 1644 Principia Philosophiae, where he also provides a clear explanation of his intent in a margin note. Fuller forms of the phrase are due to other authors. [Formatting note: cogito variants in this section are highlighted in boldface to facilitate comparison; italics only as in originals.]

In Discours de la Méthode (1637)[edit]

The phrase first appeared (in French) in Descartes' 1637 Discours de la Méthode (full title in English: Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason, and Seeking Truth in the Sciences). From the first paragraph of Part IV:

- French: "… Ainsi, à cause que nos sens nous trompent quelquefois, je voulus supposer qu'il n'y avoit aucune chose qui fût telle qu'ils nous la font imaginer; et parce qu'il y a des hommes qui se méprennent en raisonnant, même touchant les plus simples matières de géométrie, et y font des paralogismes, jugeant que j'étois sujet à faillir autant qu'aucun autre, je rejetai comme fausses toutes les raisons que j'avois prises auparavant pour démonstrations; et enfin, considérant que toutes les mêmes pensées que nous avons étant éveillés nous peuvent aussi venir quand nous dormons, sans qu'il y en ait aucune pour lors qui soit vraie, je me résolus de feindre que toutes les choses qui m'étoient jamais entrées en l'esprit n'étoient non plus vraies que les illusions de mes songes. Mais aussitôt après je pris garde que, pendant que je voulois ainsi penser que tout étoit faux, il falloit nécessairement que moi qui le pensois fusse quelque chose; et remarquant que cette vérité, je pense, donc je suis [italics in original], étoit si ferme et si assurée, que toutes les plus extravagantes suppositions des sceptiques n'étoient pas capables de l'ébranler, je jugeai que je pouvois la recevoir sans scrupule pour le premier principe de la philosophie que je cherchois."

- English: "… Accordingly, seeing that our senses sometimes deceive us, I was willing to suppose that there existed nothing really such as they presented to us; and because some men err in reasoning, and fall into paralogisms, even on the simplest matters of geometry, I, convinced that I was as open to error as any other, rejected as false all the reasonings I had hitherto taken for demonstrations; and finally, when I considered that the very same thoughts (presentations) which we experience when awake may also be experienced when we are asleep, while there is at that time not one of them true, I supposed that all the objects (presentations) that had ever entered into my mind when awake, had in them no more truth than the illusions of my dreams. But immediately upon this I observed that, whilst I thus wished to think that all was false, it was absolutely necessary that I, who thus thought, should be somewhat; and as I observed that this truth, I think, therefore I am, was so certain and of such evidence that no ground of doubt, however extravagant, could be alleged by the sceptics capable of shaking it, I concluded that I might, without scruple, accept it as the first principle of the philosophy of which I was in search."[b][c]

In Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (1641)[edit]

In 1641, Descartes published (in Latin) Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (English: Meditations on first philosophy) in which he referred to the proposition, though not explicitly as "cogito ergo sum" in Meditation II:

- Latin: "… hoc pronuntiatum: ego sum, ego existo, quoties a me profertur, vel mente concipitur, necessario esse verum."

- English: "… this proposition: I am, I exist, whenever it is uttered from me, or conceived by the mind, necessarily is true."[d]

In Principia Philosophiae (1644)[edit]

In 1644, Descartes published (in Latin), Principia Philosophiae (English: Principles of Philosophy) where the phrase "ego cogito, ergo sum" appears in Part 1, article 7:

- Latin: "Sic autem rejicientes illa omnia, de quibus aliquo modo possumus dubitare, ac etiam, falsa esse fingentes, facilè quidem, supponimus nullum esse Deum, nullum coelum, nulla corpora; nosque etiam ipsos, non habere manus, nec pedes, nec denique ullum corpus, non autem ideò nos qui talia cogitamus nihil esse: repugnat enim ut putemus id quod cogitat eo ipso tempore quo cogitat non existere. Ac proinde haec cognitio, ego cogito, ergo sum [italics in original], est omnium prima & certissima, quae cuilibet ordine philosophanti occurrat."

- English: "While we thus reject all of which we can entertain the smallest doubt, and even imagine that it is false, we easily indeed suppose that there is neither God, nor sky, nor bodies, and that we ourselves even have neither hands nor feet, nor, finally, a body; but we cannot in the same way suppose that we are not while we doubt of the truth of these things; for there is a repugnance in conceiving that what thinks does not exist at the very time when it thinks. Accordingly, the knowledge, I think, therefore I am, is the first and most certain that occurs to one who philosophizes orderly."[e]

Descartes' margin note for the above paragraph is:

- Latin: "Non posse à nobis dubitari, quin existamus dum dubitamus: at que hoc esse primum quod ordine philosophando cognoscimus."

- English: "That we cannot doubt of our existence while we doubt, and that this is the first knowledge we acquire when we philosophize in order."[e]

Other forms[edit]

The proposition is sometimes given as "dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum". This fuller form was penned by the eloquent French literary critic,Antoine Léonard Thomas, in an award-winning 1765 essay in praise of Descartes, where it appeared as "Puisque je doute, je pense; puisque je pense, j'existe." In English, this is "Since I doubt, I think; since I think I exist"; with rearrangement and compaction, "I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am", or in Latin, "dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum".[f]

A further expansion, "dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum—res cogitans" ("…—a thinking thing") extends the cogito with Descartes' statement in the subsequent Meditation, "Ego sum res cogitans, id est dubitans, affirmans, negans, pauca intelligens, multa ignorans, volens, nolens, imaginans etiam et sentiens …", or, in English, "I am a thinking (conscious) thing, that is, a being who doubts, affirms, denies, knows a few objects, and is ignorant of many …".[g] This has been referred to as "the expanded cogito".[11]

Interpretation[edit]

The phrase cogito ergo sum is not used in Descartes' Meditations on First Philosophy but the term "the cogito" is used to refer to an argument from it. In the Meditations, Descartes phrases the conclusion of the argument as "that the proposition, I am, I exist, is necessarily truewhenever it is put forward by me or conceived in my mind." (Meditation II)

At the beginning of the second meditation, having reached what he considers to be the ultimate level of doubt — his argument from the existence of a deceiving god — Descartes examines his beliefs to see if any have survived the doubt. In his belief in his own existence, he finds that it is impossible to doubt that he exists. Even if there were a deceiving god (or an evil demon), one's belief in their own existence would be secure, for there is no way one could be deceived unless one existed in order to be deceived.

There are three important notes to keep in mind here. First, he claims only the certainty of his own existence from the first-person point of view — he has not proved the existence of other minds at this point. This is something that has to be thought through by each of us for ourselves, as we follow the course of the meditations. Second, he does not say that his existence is necessary; he says that if he thinks, then necessarily he exists (see the instantiation principle). Third, this proposition "I am, I exist" is held true not based on a deduction (as mentioned above) or on empirical induction but on the clarity and self-evidence of the proposition. Descartes does not use this first certainty, the cogito, as a foundation upon which to build further knowledge; rather, it is the firm ground upon which he can stand as he works to restore his beliefs. As he puts it:

According to many Descartes specialists, including Étienne Gilson, the goal of Descartes in establishing this first truth is to demonstrate the capacity of his criterion — the immediate clarity and distinctiveness of self-evident propositions — to establish true and justified propositions despite having adopted a method of generalized doubt. As a consequence of this demonstration, Descartes considers science and mathematics to be justified to the extent that their proposals are established on a similarly immediate clarity, distinctiveness, and self-evidence that presents itself to the mind. The originality of Descartes' thinking, therefore, is not so much in expressing the cogito — a feat accomplished by other predecessors, as we shall see — but on using the cogito as demonstrating the most fundamental epistemological principle, that science and mathematics are justified by relying on clarity, distinctiveness, and self-evidence. Baruch Spinoza in "Principia philosophiae cartesianae" at its Prolegomenon identified "cogito ergo sum" the "ego sum cogitans" (I am a thinking being) as the thinking substance with hisontological interpretation. It can also be considered that Cogito ergo sum is needed before any living being can go further in life".[12][citation needed]

Predecessors[edit]

Although the idea expressed in cogito ergo sum is widely attributed to Descartes, he was not the first to mention it. Plato spoke about the "knowledge of knowledge" (Greek νόησις νοήσεως - nóesis noéseos) and Aristotle explains the idea in full length:

Augustine of Hippo in De Civitate Dei writes Si […] fallor, sum ("If I am mistaken, I am") (book XI, 26), and also anticipates modern refutations of the concept. Furthermore, in the Enchiridion Augustine attempts to refute skepticism by stating, "[B]y not positively affirming that they are alive, the skeptics ward off the appearance of error in themselves, yet they do make errors simply by showing themselves alive; one cannot err who is not alive. That we live is therefore not only true, but it is altogether certain as well" (Chapter 7 section 20). Another predecessor wasAvicenna's "Floating Man" thought experiment on human self-awareness and self-consciousness.[13]

The 8th Century Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara wrote in a similar fashion, No one thinks, 'I am not', arguing that one's existence cannot be doubted, as there must be someone there to doubt.[14]

Criticisms[edit]

There have been a number of criticisms of the argument. One concerns the nature of the step from "I am thinking" to "I exist." The contention is that this is a syllogistic inference, for it appears to require the extra premise: "Whatever has the property of thinking, exists", a premise Descartes did not justify. In fact, he conceded that there would indeed be an extra premise needed, but denied that the cogito is a syllogism (see below).

To argue that the cogito is not a syllogism, one may call it self-evident that "Whatever has the property of thinking, exists". In plain English, it seems incoherent to actually doubt that one exists and is doubting. Strict skeptics maintain that only the property of 'thinking' is indubitably a property of the meditator (presumably, they imagine it possible that a thing thinks but does not exist). This countercriticism is similar to the ideas of Jaakko Hintikka, who offers a nonsyllogistic interpretation of cogito ergo sum. He claimed that one simply cannot doubt the proposition "I exist". To be mistaken about the proposition would mean something impossible: I do not exist, but I am still wrong.

Perhaps a more relevant contention is whether the "I" to which Descartes refers is justified. In Descartes, The Project of Pure Enquiry, Bernard Williams provides a history and full evaluation of this issue. Apparently, the first scholar who raised the problem was Pierre Gassendi. Hepoints out that recognition that one has a set of thoughts does not imply that one is a particular thinker or another. Were we to move from the observation that there is thinking occurring to the attribution of this thinking to a particular agent, we would simply assume what we set out to prove, namely, that there exists a particular person endowed with the capacity for thought . In other words, the only claim that is indubitable here is the agent-independent claim that there is cognitive activity present.[15] The objection, as presented by Georg Lichtenberg, is that rather than supposing an entity that is thinking, Descartes should have said: "thinking is occurring." That is, whatever the force of the cogito, Descartes draws too much from it; the existence of a thinking thing, the reference of the "I," is more than the cogito can justify. Friedrich Nietzsche criticized the phrase in that it presupposes that there is an "I", that there is such an activity as "thinking", and that "I" know what "thinking" is. He suggested a more appropriate phrase would be "it thinks." In other words the "I" in "I think" could be similar to the "It" in "It is raining." David Hume claims that the philosophers who argue for a self that can be found using reason are confusing "similarity" with "identity". This means that the similarity of our thoughts and the continuity of them in this similarity do not mean that we can identify ourselves as a self but that our thoughts are similar.[citation needed]

Williams' argument in detail[edit]

In addition to the preceding two arguments against the cogito, other arguments have been advanced by Bernard Williams. He claims, for example, that what we are dealing with when we talk of thought, or when we say "I am thinking," is something conceivable from a third-personperspective; namely objective "thought-events" in the former case, and an objective thinker in the latter.

Williams provides a meticulous and exhaustive examination of this objection. He argues, first, that it is impossible to make sense of "there is thinking" without relativizing it to something. However, this something cannot be Cartesian egos, because it is impossible to differentiate objectively between things just on the basis of the pure content of consciousness.

The obvious problem is that, through introspection, or our experience of consciousness, we have no way of moving to conclude the existence of any third-personal fact, to conceive of which would require something above and beyond just the purely subjective contents of the mind.

Søren Kierkegaard's critique[edit]

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard provided a critical response to the cogito.[16] Kierkegaard argues that the cogito already presupposes the existence of "I", and therefore concluding with existence is logically trivial. Kierkegaard's argument can be made clearer if one extracts the premise "I think" into two further premises:

Where "x" is used as a placeholder in order to disambiguate the "I" from the thinking thing.[17]

Here, the cogito has already assumed the "I"'s existence as that which thinks. For Kierkegaard, Descartes is merely "developing the content of a concept", namely that the "I", which already exists, thinks.[18]

Kierkegaard argues that the value of the cogito is not its logical argument, but its psychological appeal: a thought must have something that exists to think the thought. It is psychologically difficult to think "I do not exist". But as Kierkegaard argues, the proper logical flow of argument is that existence is already assumed or presupposed in order for thinking to occur, not that existence is concluded from that thinking.[19]

John Macmurray's Rejection[edit]

The Scottish philosopher John Macmurray rejects the cogito outright in order to place action at the center of a philosophical system. "We must reject this, both as standpoint and as method. If this be philosophy, then philosophy is a bubble floating in an atmosphere of unreality." [20]The reliance on thought creates an irreconcilable dualism between thought and action in which the unity of experience is lost. In order to formulate a more adequate cogito, Macmurray proposes the substitution of "I do" for "I think".

Skepticism[edit]

Many philosophical skeptics and particularly radical skeptics would say that indubitable knowledge does not exist, is impossible, or has not been found yet, and would apply this criticism to the assertion that the "cogito" is beyond doubt.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The cogito ergo sum phrase was not capitalized by Descartes in his Principia Philosophiae.[21]

- ^ This translation, from Discours de la méthode at Project Gutenberg, inserted the uppercase Latin phrase “COGITO ERGO SUM” in parentheses after the "I think, therefore I am". However, as this was not in the original French, it has been removed here.

- ^ The 1637 Discours was translated to Latin in the 1644 Specimina Philosophiae[2] but this is not referenced here because of issues raised regarding translation quality.[3]

- ^ This combines, for clarity and to retain phrase ordering, the translations of Cress[4] and Haldane.[5]

- ^ a b Translation from The Principles of Philosophy at Project Gutenberg.

- ^ The 1765 work, Éloge de René Descartes,[6] by Antoine Léonard Thomas, was awarded the 1765 Le Prix De L'académie Française and republished in the 1826 compilation of Descartes' work, Oeuvres de Descartes[7] by Victor Cousin. The French text is available in more accessible format at Project Gutenberg. The compilation by Cousin is credited with a revival of interest in Descartes.[8][9]

- ^ This translation by Veitch[10] is the first English translation from Descartes as "I am a thinking thing".

References[edit]

- ^ Burns, William E. (2001). The scientific revolution: an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 84. ISBN 0-87436-875-8.

- ^ Descartes, René (1644). Specimina philosophiae.

- ^ Vermeulen, Corinna Lucia (2006). René Descartes, Specimina philosophiae. Introduction and Critical Edition (Dissertation, Utrecht University).

- ^ Descartes, René (1986). Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. Translated by Donald A. Cress. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-60384-551-9.

- ^ Descartes, René (1960). Meditations on first philosophy. Translated by Elizabeth S. Haldane. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-61536-207-3.

- ^ Thomas, Antoine Léonard (1765). Éloge de René Descartes.

- ^ Cousin, Victor (1824). Oeuvres de Descartes.

- ^ The Edinburgh Review for July, 1890 … October, 1890. Leonard Scott Publication Co. 1890. p. 469.

- ^ Descartes, René (2007). The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Translated by Lisa Shapiro. University of Chicago Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0226204420.

- ^ Veitch, John (1880). The Method, Meditations and Selections from the Principles of René Descartes (7th ed.). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. p. 115.

- ^ Kline, George, L. (1967). Naturalism and Historical Understanding. SUNY Press. p. 85.

|first1=missing|last1=in Editors list (help) - ^ Vesey, Nicholas (2011). Developing Consciousness. United Kingdom: O-Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84694-461-1.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein and Leaman, Oliver (1996), History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 315, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13159-6.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S. (1948), Indian Philosophy, vol II, p. 476, George Allen & Unwin Ltd,

- ^ Fisher, Saul (2005). "Pierre Gassendi". Retrieved 1 December 2014. from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Philosophical Fragments. Trans. Hong, Princeton, 1985. p. 38-42.

- ^ Schönbaumsfeld, Genia. A Confusion of the Spheres. Oxford, 2007. p.168-170.

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Philosophical Fragments. Trans. Hong, Princeton, 1985. p. 40.

- ^ Archie, Lee C., "Søren Kierkegaard, God's Existence Cannot Be Proved". Philosophy of Religion. Lander Philosophy, 2006.

- ^ Macmurray, John. The Self as Agent. Humanity books, 1991. p. 78.

- ^ Descartes, René (1644). Principia Philosophiae.

Further reading[edit]

- Abraham, W.E. "Disentangling the Cogito", Mind 83:329 (1974)

- Boufoy-Bastick, Z. Introducing 'Applicable Knowledge' as a Challenge to the Attainment of Absolute Knowledge , Sophia Journal of Philosophy, VIII (2005), pp 39–52.

- Descartes, R. (translated by John Cottingham), Meditations on First Philosophy, in The Philosophical Writings of Descartes vol. II (edited Cottingham, Stoothoff, and Murdoch; Cambridge University Press, 1984) ISBN 0-521-28808-8

- Hatfield, G. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Descartes and the Meditations (Routledge, 2003) ISBN 0-415-11192-7

- Kierkegaard, S. Concluding Unscientific Postscript (Princeton, 1985) ISBN 978-0-691-02081-5

- Kierkegaard, S. Philosophical Fragments (Princeton, 1985) ISBN 978-0-691-02036-5

- Williams, B. Descartes, The Project of Pure Enquiry (Penguin, 1978) OCLC 4025089

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- Macmurray, John. "The Self as Agent" 1951

External links[edit]

- See External Links for Descartes' 1637 Discourse on the Method

- See External Links for Descartes' 1641 Meditations on First Philosophy

- See External Links for Descartes' 1644 Principles of Philosophy

- Descartes' Epistemology entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Descartes — The Cogito Argument

fr https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito_ergo_sum

This page was last modified on 10 March 2015, at 05:27.

>>>

다음 백과

http://100.daum.net/search/search.do?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버지식백과

http://terms.naver.com/search.nhn?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

한국 위키백과

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito_ergo_sum

영어 위키 백과

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito_ergo_sum

네이버 한자

http://hanja.naver.com/search?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버 지식

http://kin.naver.com/search/list.nhn?cs=utf8&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버 영어사전

http://endic.naver.com/search.nhn?isOnlyViewEE=N&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

구글

https://www.google.co.kr/?gws_rd=ssl#newwindow=1&q=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버

http://search.naver.com/search.naver?where=nexearch&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

다음

http://search.daum.net/search?w=tot&q=Cogito+ergo+sum

다음 백과

Cogito ergo sum

네이버지식백과

Cogito ergo sum

한국 위키백과

Cogito ergo sum

영어 위키 백과

Cogito ergo sum

네이버 한자

Cogito ergo sum

네이버 지식

Cogito ergo sum

네이버 영어사전

Cogito ergo sum

구글

Cogito ergo sum

네이버

Cogito ergo sum

다음

Cogito ergo sum

다음 백과

http://100.daum.net/search/search.do?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버지식백과

http://terms.naver.com/search.nhn?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

한국 위키백과

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito_ergo_sum

영어 위키 백과

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cogito_ergo_sum

네이버 한자

http://hanja.naver.com/search?query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버 지식

http://kin.naver.com/search/list.nhn?cs=utf8&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버 영어사전

http://endic.naver.com/search.nhn?isOnlyViewEE=N&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

구글

https://www.google.co.kr/?gws_rd=ssl#newwindow=1&q=Cogito+ergo+sum

네이버

http://search.naver.com/search.naver?where=nexearch&query=Cogito+ergo+sum

다음

http://search.daum.net/search?w=tot&q=Cogito+ergo+sum

>>>

르네 데카르트

>>>

참고 https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/르네_데카르트

르네 데카르트

Portrait after Frans Hals, 1648[1] | |

| 이름 | 르네 데카르트 |

|---|---|

| 출생 | 1596년 3월 31일 |

| 사망 | 1650년 2월 11일 (53세) |

| 시대 | 17세기 철학 |

| 지역 | 서양철학 |

| 학파 | 데카르트주의, 합리주의 철학, 기초주의 |

| 연구 분야 | 형이상학, 인식론, 수학 |

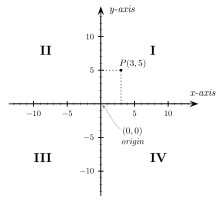

| 주요 업적 | Cogito, ergo sum, 데카르트적 회의, 직교 좌표계, 이원병존주의, 신의 존재에 대한 존재론적 논증, 보편수학, 데카르트 정엽선 |

| 서명 | |

| 위키인용집에 이 문서와 관련된 문서가 있습니다. |

르네 데카르트(프랑스어: René Descartes [ʁəne dekaʁt][*], 라틴어: Renatus Cartesius, 1596년 3월 31일 - 1650년 2월 11일)는

프랑스의 물리학자, 근대 철학의 아버지, 해석기하학의 창시자로 불린다.

그는 합리론의 대표주자이며

본인의 대표 저서 《방법서설》에서

‘나는 생각한다, 고로 존재한다.(Cogito ergo sum)’는 계몽사상의 '자율적이고 합리적인 주체'의 근본 원리를 처음으로 확립한 것으로 유명하다.

1606년 예수회가 운영하는 라 플레쉬 콜레즈(Collège la Flèche)에 입학하여

1614년까지 8년간에 걸쳐 철저한 중세식 그리고 인본주의 교육을 받게 된다.

미완성 논문 <정신지도의 규칙>을 쓴다.

1628년 말, 네덜란드로 돌아온 그는 다시 저술활동에 몰두해

《세계론》(Traite du monde)을 프랑스어로 출판한다.

1637년에는 《방법서설》에 굴절광학, 기상학, 기하학의 세 가지 부분을 덧붙여 익명을 출판했다가

후에 프랑스어로 《방법서설》을 완성한다.

1644년 자신의 철학을 체계적으로 정리하여

라틴어로 《철학원리》를 출판한다.

그 후 그는 여러 사람과 편지로 자신의 생각을 전하곤 했는데,

최고선에 관한 자신의 생각들을 편지로 보낸 것들이 모여

1649년 출판된 그의 마지막 책, 《정념론》(Les passions de l'ame)이 된다.

1650년 2월 11일, 그는 폐렴에 걸려 54세의 나이로 세상을 떠난다.

목차

[숨기기]생애[편집]

데카르트는 1596년 투렌 지방(Touraine)의 투르 인근에 있는 소도시 라에(La Haye, 현재 그의 이름을 빌어 Descartes[1])의 법관 귀족 가문에서 태어났다. 그의 아버지는 브흐따뉴의 헨느(Renne) 시의원이었으며, 어머니는 그가 태어난 지 14달이 못되어 세상을 떴다. 이후 그는 외할머니 밑에서 성장했으며, 어린 시절 몸이 무척 허약했다고 전해진다. 1606년 그는 예수회가 운영하는 라 플레쉬 콜레즈(Collège la Flèche)에 입학하여 1614년까지 8년간에 걸쳐 철저하게 중세식 그리고 인본주의 교육을 받게 된다. 5년간 라틴어, 수사학, 고전 작가 수업을 받았고 3년간 변증론에서 비롯하여 자연철학, 형이상학 그리고 윤리학을 포괄하는 철학 수업을 받았다. 그가 이 시기에 받은 교육은 후에 그의 저서 여기 저기에 흔적을 남기게 된다 (특히 《방법서설》에 많은 영향을 끼쳤다.)

라 플레쉬를 졸업한 후 뿌아띠에(Poitiers) 대학 법학과에 입학해 수학·자연 과학·법률학·스콜라 철학 등을 배우고, 수학만이 명증적인 지식이라고 생각하였다. 1616년에 리상스(Licence)를 취득한다. 이후 그는 '세상이라는 커다란 책'으로부터 실질적인 지식을 얻고자 학교밖으로 나갔고, 다시는 제도권 교육으로 돌아오지 않았다.[5] 졸업 후 지원병으로 입대하여 네덜란드에 갔으며, 30년 전쟁이 일어나자 독일에 출정하였다. 1619년 네덜란드를 여행하면서 첫 작품 짧은 《음악 개론》(Compendium Musicae)을 썼다. 같은 해에 독일 바이에른의 막시밀리안 군대에 들어가기 위해 프랑크푸르트를 거쳐 여행하던 중 11월 10일 울름의 한 여관에서 자신의 삶의 길을 밝혀 주는 꿈을 꾸게 된다. 데카르트는 여기서 삶의 목표를 학문에 두기로 결심하였다.

1620년 제대하고 프랑스에 귀환, 1626년부터 파리에서 수학·자연 과학, 특히 광학을 연구하였다. 1627년에 다시 종군한 후, 1628년 단편 <정신 지도의 법칙>을 집필, 자신의 방법론 체계를 세우려 하였다. 같은 해 가을, 연구와 사색의 자유를 찾아 네덜란드로 건너가 철학 연구에 몰두하였다. 《방법서설》, 《성찰》, 《철학의 원리》, 《정념론》 등은 네덜란드에 약 20년간 머물러 있는 동안에 저술한 것이다.

1628년 겨울에 데카르트는 로마 가톨릭 교회의 영향 밑에 있는 프랑스를 떠나, 자유로운 학문 분위기가 지배적인 네덜란드로 이주했다. 네덜란드에서암스테르담, 하아렘 (네덜란드)|하아렘, 에그몬드 (네덜란드)|에그몬드 등의 도시로 여러 차례 주거지를 옮기면서 더러는 개인 교사로 혹은 은둔 학자로 생활을 했다. 이 시기 (1630년 - 1633년)에 자연과학에 관한 책 '《세계》를 집필한 것으로 여겨지며, 이 책에서 그는 코페르니쿠스와 갈릴레오 갈릴레이가 주장한 지동설을 바탕으로 세계에 관한 자신의 견해를 진술했다.

1637년부터 테카르트는 존재론과 인식론 문제에 몰두한 것으로 보이는데, 이 해에 《방법서설》을 출판했다. 존재론과 인식론에 관한 연구 결과는1641년 《제1 철학에 관한 성찰》(Meditationes: 후에 Meditationes de prima philosophia)이란 제목의 책으로 출판하게 된다.

1649년 스웨던 여왕 크리스티나의 초청을 받아 스톡홀름에 부임하여 여왕에게 철학을 강의하고, 아카데미 창립에도 관여하였으나, 1650년 초 폐렴으로 사망하였다.

그는 학문 중에서 수학만이 확실한 것으로 철학도 수학과 같이 분명하고 명확히 드러나는 진리를 출발점으로 해야 한다고 생각하였다. 그로 인해 그는 기존의 모든 지식을 의심하였는데, 그렇지만 최후의 의심할 수 없는 명제, "나는 생각한다. 고로 존재한다"에 도달, 이것이 철학의 근본 기초라고 설명하였다. 그 기계적 우주관은 18세기 프랑스의 유물론에 영향을 주었다. 그는 '근대 철학의 아버지'라고 불리며, 수학에 있어서는 해석 기하학을 창시하여 근대 수학의 길을 열어놓았다.[6]

데카르트는 수학자로서도 유명하지만 철학자로의 삶도 살았다. 데카르트는 가장 확실하고 의심할 여지가 없는 진리를 찾으려 했다. 그래서 택한 방법이 진리가 아닌 것들을 소거하는 것인데, 그 방법은 저서 《방법서설》에 잘 나타나 있다. 데카르트는 확실한 진리를 찾으려 불확실하다고 생각하는 감각도 배제 했는데, 이는 감각도 반드시 맞는 것이라고 확신할 수 없기 때문이다. 그리하여 도달한 결론이 "나는 생각한다, 고로 존재한다." 이다. 이 결론에 도달한 것은 《방법서설》에도 잘 나타나 있다. 전능한 악마가 인간을 속이려 한다고 해도, 악마가 속이려면 생각하는 자신이 필요하다는 것이다.('제일철학을 위한 성찰'에 나와있다.) 이 명제는 근대 철학을 대표하는 명제이며, 데카르트 이후 근대 철학은 이 명제에 절대적인 영향을 받았다. 특히 데카르트가 사용한 관념이라는 개념은 칸트와 같은 철학자에도 큰 영향을 미쳤다.

데카르트는 본유관념과 인위관념, 외래관념을 분리하였다. 여기서 외래관념은 밖에서 오는 관념을 말하고 인위관념은 자신의 의지에 따라 만들어 내는 것을 말하며, 본유관념은 태어나면서 부터 존재하는 관념을 말한다. 본유관념은 '삼각형의 꼭짓점은 세개이다.', '정육면체의 면은 여섯개 이다.', '유클리드 기하학에서 두 평행선은 서로 만나지 않는다.' 와 같은 것으로, 언제나 확실하게 참인 것으로 판단되는 것을 말한다. 덧붙여 데카르트는 신의 관념도 확실한 것으로 보았다. 그는 존재론적 증명을 통하여 신이 있음을 증명하였다. 그러나 이러한 존재론적 증명은 나중에 칸트의 비판을 받았다.

데카르트는 주체와 대상을 일치시키려 실체를 두 부분으로 나누었다. 바로 연장과 사유이다. 연장은 구체적인 부피와 같은 공간을 차지하는 실체를 말하고, 사유는 연장과 달리 부피와 같은 것이 없는 실체를 말한다. 데카르트는 인간을 연장과 사유가 함께 있는 것으로 보았다. 여기서 사유는 몸을 제어시키는 것으로 보았다. 또한 몸과 사유를 이어주는 부분을 송과선으로 보았는데, 데카르트 이후 철학자들은 이 송과선을 몸으로 볼 것인지, 아닌지에 대해서 논란을 벌이기도 했다.

일화[편집]

이름[편집]

데카르트가 태어난 지 얼마 되지 않아 그의 어머니는 폐병으로 세상을 떠났다. 당시 갓난아기였던 그는 병에 걸려 목숨이 위태로웠고 의사마저도 소생할 가망이 없다고 진단을 내렸다. 다행히도 마음씨 고운 한 간호사의 보살핌 덕분에 그는 겨우 살아남을 수 있었다. 아마도 이때의 일로 인해 그의 이름을 ‘중생(重生)’이란 뜻의 데카르트로 지은 것으로 보인다.

특성[편집]

그는 주변 사물에 대한 호기심이 강해 어려서부터 조용한 곳에서 골똘히 생각에 잠기는 버릇이 있었다. 그의 부친은 그에게 철학가 기질이 있음을 발견하고 ‘꼬마 철학가’라는 별명을 붙여 주었다. 하지만 부자의 관계는 그다지 좋지 않았는지 그는 스스로 형제 중에서 아버지가 가장 싫어하는 아이였다고 말한 바 있다. 그리고 형제들과도 살가운 정을 나누지 못했다. 이런 이유 때문인지 그는 자주 집을 떠나 혼자 여행을 다녔고 친구들에게 마음을 쏟았다. 어린 시절 가지고 놀던 장난감 중에서 사팔뜨기 인형을 제일 좋아했던 그는 커서도 유독 장애인들에게 호감을 보였다.

수학[편집]

8세 때 데카르트는 라 플레슈 La Fleche의 예수회 학교에 입학하여 고전문학과 수학을 공부했다. 데카르트의 선생님은 그를 똑똑하고 부지런하며, 품행이 단정하고, 내성적이지만 승부욕이 강하고, 수학에 특별한 재능이 있다고 평가했다. 그는 학교의 구시대적 교육방식에 불만을 참지 못하고 자신이 배운 교과서를 잡다한 지식의 쓰레기라고 비난을 퍼부었다. 그는 1613년에 파리로 가서 법률을 배웠고 1616년 푸아티에poitier 대학교를 졸업했다. 그의 아버지는 그의 식견을 높이기 위해 1617년 그를 다시 파리로 보냈다. 그러나 그는 화려한 도시 생활에 별다른 흥미를 느끼지 못했다. 수학과 관련된 도박만이 그의 유일한 위안이었다. 1617년의 어느 날 한가로이 길을 걷던 데카르트는 벽에 붙은 광고지를 발견했다. 호기심이 발동한 그는 무엇인지 확인하기 위해 광고지가 붙은 곳으로 다가갔다. 광고는 네덜란드어로 적혀 있어서 내용을 알 수 없었다. 그는 네덜란드어를 아는 사람에게 도움을 구하기 위해 주위를 둘러보았다. 마침 자신을 향해 걸어오는 행인을 발견한 데카르트는 광고에 적힌 내용을 물었다. 뜻밖에도 그 사람은 네덜란드 대학교 교장이었고 데카르트에게 광고 내용을 설명해 주었다. 광고는 어려운 기하학 문제가 적혀 있었고 이 문제를 푸는 사람에게 사례하겠다는 내용이었다. 상황을 이해한 데카르트는 단지 몇 시간 만에 문제를 풀었고 자신에게 수학적 재능이 있음을 발견했다.

해석기하학[편집]

"내가 바라는 것은 평온과 휴식뿐이다."라고 말한 수학의 새로운 국면으로 이끈 수학자 데카르트는 어린 시절 몸이 허약해 눈뜨기 힘든 아침 시간, 교장 선생님의 허락을 받아 같은 또래의 보통 소년들과는 달리 제 좋을 때까지 침대에 누워 휴식을 취하였다. 중년이 된 데카르트는 학교생활을 되돌아보고 나서 이 길고 조용한 아침의 명상이 자신의 철학과 수학의 참다운 원천이었다고 얘기한다. 그 예에 해당하는 일화가 있다. 그가 처음으로 도입한좌표 개념의 발견과 관련된 일화인데, 침대에 누워 천장에 붙어있는 파리를 보고 파리의 위치를 나타내는 일반적인 방법을 찾으려고 애쓰다가 '좌표'라는 발상을 하게 되었다는 것이다.

철학[편집]

어느 날 데카르트는 문득 자신에게 이상한 성향이 있음을 자각한다. 사시(斜視: 사팔뜨기)라는 신체적 결함을 가진 사람만 보면 왠지 더 친근감을 느끼고 이유 없이 호의를 베푼다는 사실을 발견한 것이다. 그 이유를 찾으려고 애쓰던 데카르트는 결국 어린 시절에 한 소녀를 사랑한 적이 있었고, 그녀의 눈이 사시였음을 기억해 낸다. 사랑에 빠진 데카르트에게 소녀의 신체적 결함은 전혀 문제되지 않았다. 사랑의 감정이 그녀의 신체적 결점을 압도하여, 사시라는 결점은 훗날 무의식적으로 좋은 감정을 촉발하는 계기가 되었던 것이다. 경험의 지배를 받는 인간은 어떤 선택의 순간에 부닥쳤을 때, 자신도 모르는 사이에 과거에 받은 감정적 충격이나 상처 때문에 종종 객관적인 판단을 내리지 못한다.

근대철학의 아버지, ‘철학의 왕자’로 군림했던 데카르트는 이 사소한 일화를 통해, 감정이 어떻게 이성의 판단을 방해하는지 깨닫는다.

수학과 철학[편집]

르네 데카르트는 30년전쟁 때 울름가 주변의 전쟁터를 돌아다녔다. 그곳은 겨울에 너무나 추웠다. 그가 술회한 바에 의하면, 그는 어느 벽난로 속으로 기어들어갔고, 그 난로 속에서 잠이 들었다가 세 가지 꿈을 꾸었다. 첫 번째 꿈에서 데카르트는 심한 바람이 불고 있는 거리 한 모퉁이에 서 있었다. 그는 오른쪽 다리가 약하여 제대로 서 있을 수 없었는데 그 근처에는 바람에 흔들리지 않는 한 사람이 있어 데카르트 자신이 그 쪽으로 날아가 버렸다. 잠깐 눈을 떴다가 다시 잠에 빠져들었는데, 두 번째 꿈에서 그는 미신으로 흐려지지 않는 과학의 눈으로 무서운 폭풍을 지켜보고 있었다. 이 폭풍은 일단 그 정체가 폭로되고 난 후에는 그에게 아무런 해도 끼치지 못한다는 사실을 그는 깨달았다. 세 번째로 꿈을 꿀 때는, 테이블 위에 사전과 그 옆에 다른 책이 놓여 있는데 ‘나는 어떠한 생활을 보내야 할 것인가?’라는 글귀가 눈에 들어오며 낯선 사람이 그에게 다가와 ‘Quiet Non’(그는 이것을 인간의 지식과 학문의‘참과 거짓’이라 해석함)으로 시작하는 시를 보여주었다. 그는 세 번째 꿈에서 깨어난 후에 이미 꾼 꿈들의 의미를 생각하였는데 첫 번째 꿈은 과거의 오류에 대한 경고이며, 두 번째 꿈은 그를 사로잡은 진실의 정신이 내습한다는 것이고, 마지막 꿈은 모든 과학의 가치와 참된 지기에의 길을 열 것을 명령하는 것이라고 생각하였다. 이 사건은 데카르트가 참된 지식으로의 접근법에 대하여 스스로가 정당성을 확신하고 있음을 보여주고 있다.

그는 이미 이 꿈들을 꾸기 8개월 전 베크만에게 보낸 보고에 ‘앞으로는 기하학에서 발견해야 할 것은 거의 아무것도 남지 않을 것이다.’라고 자신의 계획을 공언하였다. 기하학과 대수학의 결합으로 두 개의 학문 영역을 하나의 학문으로 파악하는 데 성공한 데카르트는 더 나아가 모든 학문을 하나의방법론으로 통합하려 하였다. 모든 문제는 동일하고 보편적인 ‘수학적’ 방법으로 해결할 수 있다는 생각이었다. 이 방법을 그는 '보편수학’이라고 불렀다.

하지만 철학의 진술은 수학의 진술처럼 아주 기초적이고, 논리적이고, 엄격해야만 하는데 아직 그러지 못했다. 철학의 기초를 확립하기 위해서 그는 우선 모든 것들에 대해 회의했다. 그럼으로써 모든 근본 중의 근본을 발견했다. 다시 말해서 그는 근대철학의 토대를 발견했으며, 이 토대 위에 하나의 새로운 철학교회를 세웠다.

죽음[편집]

1649년 2월, 스웨덴의 여왕 크리스티나는 데카르트를 스웨덴 황궁으로 초대했다. “크리스티나는 학문에 대한 열정과 해박한 지식을 지녔다. 그녀는 여왕으로서 위대한 학자의 시간을 뺏을 권한을 지니고 있었다. 데카르트는 그녀에게 사랑에 관한 글을 써서 바쳤는데, 이것은 그때까지 그가 무시해왔던 제목이었다.” 여왕은 일주일에 세 번 그에게서 철학 강의를 들었는데 반드시 새벽 5시에 강의하도록 명했다. 데카르트는 그동안 아침에 늦게 일어나는 습관을 가지고 있었지만 여왕의 명에 따라 일주일에 3일은 한밤중에 일어나서 스웨덴의 찬 공기를 가르며 자신의 숙소에서 여왕의 서재로 찾아가야 했다. 1650년 2월 1일, 새벽 찬 바람을 맞은 데카르트는 감기에 걸렸고, 곧바로 폐렴으로 악화되었다. 데카르트는 1650년 2월 11일 스톡홀름에서 세상을 떠났다. 그의 유골은 1667년에 파리에 돌아왔고 주느비에브 뒤몽 성당에 안치되었다. 1799년 프랑스 정부는 그의 유해를 프랑스 역사관으로 옮겨 프랑스 역사상 위대한 인물들과 함께 모셨다. 1819년 이후 그의 유골은 다시 생 제르맹 데프레 성당에 안치되었다. 그의 묘비에는 이런 글이 적혀 있다. “데카르트, 유럽 르네상스 이후 인류를 위해 처음으로 이성의 권리를 쟁취하고 확보한 사람이다.”

업적[편집]

르네 데카르트는 근세사상의 기본 틀을 처음으로 확립함으로써 근세철학의 시조로 일컬어진다. 그는 이원론을 주장하였는데, 이는 과학적 자연관과 정신의 형이상학을 연결지어 세상을 몰가치적이고 합리적으로 보는 태도와 정신의 내면성을 강조하였다. 대륙철학의 합리주의의 근본이 된 그의 회의론은 다양한 해석으로 받아들여지고 있다. 그 중 가장 유명한 것은 '의심이 가능한 모든 믿음을 제외함으로써 기본적인 신념만을 남기는 것을 목표로 한다'는 것이었다. 그는 수학을 이러한 의심의 여지가 없는 기본 신념으로 여겨 철학을 포함한 모든 진리를 수학적인 원리로 해석하기 위해 노력했다. 또한 그는 철학 뿐만 아니라 수학, 과학적인 업적도 이룩하였다. 1625년부터 파리에 거주하며 광학을 연구한 끝에 빛의 굴절의 법칙을 발견하였다. 1637년 《방법서설》 및 이를 서론으로 하는 《굴절광학》, 《기상학》, 《기하학》의 세 시론을 출간하였다. 수학자로서의 그는 데카르트 좌표계(직교 좌표계)를 만들어 해석기하학의 창시자로 알려졌으며 방정식의 미지수에 최초로  를 사용했다. 그 뿐 아니라 그는 거듭제곱을 표현하기 위한 지수의 사용 등을 발명했다. 르네 데카르트는 다양한 여러 상황에서 적용될 수 있는 보편적인 수학을 만든 혁명적인 수학자이며 동시에 고대 그리스 과학을 모두 집대성한 철학자이자 과학자이다. 그의 보편적인 수학은 본인이 예견했듯이 광학, 천문학, 기상학, 음향학, 화학, 건축학, 물리학, 공학, 회계 등에 다양하게 응용되었으며 본인이 미처 예견하지 못했던 분야인 전기학, 인공두뇌학, 미생물학, 유전학, 경제학 등에도 응용되고 있다. 데카르트는 "나는 생각한다. 고로 존재한다"는 말로 자신의 존재를 입증하며 이 절대적인 진리를 이용해 구성요소의 진리값을 이용한 다른 진술을 증명하는 법을 개발했다. 그는 과학을 대하는 데에 있어 크기, 모양, 운동 등의 경험적인 양에 집중하고자 했다. 아리스토텔레스의 "자연은 진공을 싫어한다."는 이론에 따라 진공의 개념을 받아들이지는 않았으나 세 가지 물질의 연장이 곧 공간을 이루고 있다고 설명했다. 르네 데카르트의 글과 방법론을 곁들인 데카르트적 회의는 서양철학의 특징적인 방법 중의 하나가 되었다. 데카르트의 철학에 관한 부분은 뒤에서 다루기로 한다.

를 사용했다. 그 뿐 아니라 그는 거듭제곱을 표현하기 위한 지수의 사용 등을 발명했다. 르네 데카르트는 다양한 여러 상황에서 적용될 수 있는 보편적인 수학을 만든 혁명적인 수학자이며 동시에 고대 그리스 과학을 모두 집대성한 철학자이자 과학자이다. 그의 보편적인 수학은 본인이 예견했듯이 광학, 천문학, 기상학, 음향학, 화학, 건축학, 물리학, 공학, 회계 등에 다양하게 응용되었으며 본인이 미처 예견하지 못했던 분야인 전기학, 인공두뇌학, 미생물학, 유전학, 경제학 등에도 응용되고 있다. 데카르트는 "나는 생각한다. 고로 존재한다"는 말로 자신의 존재를 입증하며 이 절대적인 진리를 이용해 구성요소의 진리값을 이용한 다른 진술을 증명하는 법을 개발했다. 그는 과학을 대하는 데에 있어 크기, 모양, 운동 등의 경험적인 양에 집중하고자 했다. 아리스토텔레스의 "자연은 진공을 싫어한다."는 이론에 따라 진공의 개념을 받아들이지는 않았으나 세 가지 물질의 연장이 곧 공간을 이루고 있다고 설명했다. 르네 데카르트의 글과 방법론을 곁들인 데카르트적 회의는 서양철학의 특징적인 방법 중의 하나가 되었다. 데카르트의 철학에 관한 부분은 뒤에서 다루기로 한다.

수학적 업적[편집]

르네 데카르트의 가장 큰 업적 중 하나는 해석기하학의 창시이다. 《Discourse on Method》에 포함된 소논문 《La Géométrie》(1637)은 수학의 역사에 큰 공헌을 했다. 논문에서 그는 곡선에 대수 방정식을 부여하는 방법을 발견해, 모든 원추곡선을 단 한 종류의 2차 방정식으로 표시하는 데에 성공하고 그를 제시함으로써 과학과 수학을 연결하는 중요한 연결고리를 만들었다. 또한 그는 숫자(밑) 위에 작은 숫자(지수)를 씀으로써 거듭제곱을 간단하게 표현하는 방식을 생각해냈다. 그의 수학적 업적은 라이프니츠가 제안하고 뉴턴이 발전시킨 미적분학의 근간을 이루었다. "실계수의 n차방정식의 실근의 개수는 다항식  의 실수의 열사이에서 일어나는 부호변화의 수와 같거나 그 수보다 짝수 개만큼 적다."는 데카르트의 부호법칙은 다항식의 근의 개수를 구하는 데에 유용하게 사용된다. 방정식의 미지수에 처음으로

의 실수의 열사이에서 일어나는 부호변화의 수와 같거나 그 수보다 짝수 개만큼 적다."는 데카르트의 부호법칙은 다항식의 근의 개수를 구하는 데에 유용하게 사용된다. 방정식의 미지수에 처음으로  를 사용한 것도 르네 데카르트의 업적이다. 1618년 르네 데카르트는 네덜란드로 여행을 떠나 이삭 베크만을 조우했으며, 그에게 많은 문제에 수학을 적용하는 방법을 보여주었다. 그는 수학이 어떻게 류트의 음정을 맞추는 데에 정확하게 응용될 수 있는지와 무거운 물체가 물 속에 들어갔을 때 수면의 높이 변화를 나타내는 대수적인 공식을 제안했다. 또한 진공 상태에서 물체가 낙하할 때 임의의 시간에서 그 물체가 가속하는 속도를 예측하는 방법과 어떻게 회전하는 팽이가 똑바로 서있으며 이를 통해 인간이 공중에 뜰 수 있는 방법을 이야기했다. 베크만의 일기를 통해 1618년 말까지 데카르트가 이미 기하학적인 문제를 해결하는 대수 방정식의 적용을 여러 방면에 응용했다는 것을 알 수 있다. 르네 데카르트는 수학을 "불연속적인 양의 과학"으로, 기하학을 "연속적인 양의 과학"으로 보았으나 그 둘 간의 장벽은 해석기하학이 창시됨에 따라 허물어졌다. 그는 산술과 대수학은 그저 숫자의 과학이 아니라 무리수의 사용을 정의하고 새로운 수학의 가능성을 연 명제의 과학이라는 것을 깨달았다. 《방법서설(정신지도를 위한 규칙들)》을 통해 그는 수학과 모든 과학은 상호관계적이며 둘을 따로 생각하는 것보다 전체적으로 다루는 것이 쉽다고 주장했다.

를 사용한 것도 르네 데카르트의 업적이다. 1618년 르네 데카르트는 네덜란드로 여행을 떠나 이삭 베크만을 조우했으며, 그에게 많은 문제에 수학을 적용하는 방법을 보여주었다. 그는 수학이 어떻게 류트의 음정을 맞추는 데에 정확하게 응용될 수 있는지와 무거운 물체가 물 속에 들어갔을 때 수면의 높이 변화를 나타내는 대수적인 공식을 제안했다. 또한 진공 상태에서 물체가 낙하할 때 임의의 시간에서 그 물체가 가속하는 속도를 예측하는 방법과 어떻게 회전하는 팽이가 똑바로 서있으며 이를 통해 인간이 공중에 뜰 수 있는 방법을 이야기했다. 베크만의 일기를 통해 1618년 말까지 데카르트가 이미 기하학적인 문제를 해결하는 대수 방정식의 적용을 여러 방면에 응용했다는 것을 알 수 있다. 르네 데카르트는 수학을 "불연속적인 양의 과학"으로, 기하학을 "연속적인 양의 과학"으로 보았으나 그 둘 간의 장벽은 해석기하학이 창시됨에 따라 허물어졌다. 그는 산술과 대수학은 그저 숫자의 과학이 아니라 무리수의 사용을 정의하고 새로운 수학의 가능성을 연 명제의 과학이라는 것을 깨달았다. 《방법서설(정신지도를 위한 규칙들)》을 통해 그는 수학과 모든 과학은 상호관계적이며 둘을 따로 생각하는 것보다 전체적으로 다루는 것이 쉽다고 주장했다.

과학적 업적[편집]

과학자로서의 르네 데카르트는 물리학 분야에 큰 공헌을 했다. 10살 때, 라 플레슈(La Fleche)의 학교에 입학해 논리학, 윤리학, 물리학과 형이상학, 유클리드 기하학과 새로운 대수학 및 갈릴레이의 망원경에 의한 최신 업적에 이르기까지의 훌륭한 교육을 받으며 과학자로서의 초석을 다졌다. 1618년 르네는 군에 자원 입대하여 장교로서 복무하였는데, 이 때 그의 과학적 흥미는 탄도학, 음향학, 투시법, 군사기술, 항해술 등까지 발전시켰다. 그 해 겨울 아마추어 과학자이자 당시 수학의 지도자였던 이삭 베크만을 처음 만나 다시 이론적인 문제와 물리학에 흥미를 가진 이후 몇 년간 물리학분야에 있어 빛의 원리, 공학, 자유낙하 등에 관련된 여러 문제들을 해결했다. 그는 문제를 해결하는 방식에 있어 이론적 전개 방식을 사용하였는데, 이는 가장 작은 수의 원리로부터 출발하여 이미 알려져 있는 모든 사실을 설명하고, 더구나 새로운 사실의 발견으로까지 이끌어 내는 방식이다. "스넬의 법칙"이라고도 불리는 그의 굴절의 법칙이 이 때 발견되었으며, 그는 자신의 저서 《굴절광학》에서 독자적으로 증명한 "굴절의 법칙"을 언급하는 한편,시력에 관한 다양한 연구 내용을 설명했다. 그는 《천체론(Le monde)》를 통해 코페르니쿠스와 갈릴레이가 주장한 지동설을 바탕으로 하는 세계에 관한 자신의 견해를 밝혔다. 후일 뉴턴에 의해 거부된 그의 와류이론에 의하면 에테르의 미소한 입자들이 혹성이나 태양 주위에 거대한 회전흐름, 즉 소용돌이 속에 떠 있는 어린이의 보트와 같이, 이 태양의 소용돌이 속으로 운반되고, 달도 마찬가지로 지구의 주위로 운반된다는 것이다. 르네 데카르트의 물리학은 Clifford Truesdell로부터 "데카르트의 물리학은 현대적 의미의 시초이다."(Truesdell 1984,6)라는 평을 들었다. 데카르트는 사물의 본질을 외연(extension)으로 보았다. 사물에 체계적 의심을 적용해 그것의 감각적 특징들을 지워 나간다면 마지막에 남는 것은 공간의 일부를 채우고 있는 무색, 무미, 무취의 어떠한 것이라고 보았다. 그의 공간은 물질로 꽉 차있는 플레넘(plenum)으로, 불의 원소, 공기의 원소, 흙의 원소의 세 종류의 물질로 채워져 있다. 다른 어떠한 감각적 속성이 없이도 크기, 모양, 운동 등으로만 물질을 정의해 차가움, 뜨거움, 습함 등의 질적인 개념을 끌어낼 수 있을 것이라 믿은 데카르트는 플래넘을 구성하는 작은 원소들의 충돌이 자연의 크고 작은 변화들을 일으킨다고 보았다. 또한 데카르트는 그의 책에서눈에 대한 해부학적 구조를 설명하며 빛이나 외부 이미지가 동공과 내부 유리체를 거쳐 굴절되고 상이 뒤집혀 망막에 맺히고 시신경을 통해 자극이 전달되는 과정 뿐 아니라 눈이 얼마나 상을 최대화하고 또렷하게 인식하는가에 대한 과정을 현미경과 망원경의 개념에까지 확대시켰다. 책의 마지막 장에서는 렌즈 깎는 법을 설명하며 망원경과 현미경의 유용성을 언급했다. 또한 생물학 분야에서의 르네 데카르트는 윌리암, 하베이와 나란히 근대 생리학의 아버지라 불린다. 그는 전생리학의 기초가 도는 대가적 가설을 도입했다. 다양한 동물의 머리를 해부해보며 상상력과 기억이 위치하는 곳을 찾기 위한 연구를 했으며, 네덜란드에 머무른 기간 동안 많은 시간을 들여 인체를 해부했다. 데카르트는 가설적 모델 방법을 통해 육체 전체를 일종의 기계로 간주해 눈의 깜빡임과 같은 자율적인 동작 현상과 보행과 같은 복합 동작에 있어 많은 관찰과 다양한 기계론적 설명을 내세웠다. 이러한 모든 동작과 운동을 기계론적으로 설명하는 그의 방식은 근대적 생리학에 강력한 영향력을 발휘했다. 결국 그는 자연에서 영혼을 제거시켜 중세적 자연관을 밀어내고 기계적 세계관을 정당화함으로써 자연계의 만물을 물체의 위치와 운동으로 설명가능한 것으로 만드는 데에 막대한 기여를 했다.

철학[편집]

데카르트의 방법적 회의[편집]

데카르트적 회의는 르네 데카르트의 글과 방법론이 곁들여진 방법론적 회의이다. 데카르트적 회의는 자신이 믿는 바의 진실성 여부에 대해서 의심하는 체계적인 방법으로 철학의 특징적인 방법이 되었다. 이 의심의 방법은 절대적인 진실로서 받아들일 수 있는 것을 찾기 위해 자신의 모든 믿음을 의심한 르네 데카르트에 의해 서양 철학에 대중화 되었다.

특성[편집]

데카르트적 회의는 방법론적이다. 데카르트적 회의의 목적은 의심할 수 없는 것을 찾는 것으로서 의심을 절대적인 진리를 찾는 수단으로 이용하는 것이다. 특히나 경험적 정보의 오류 가능성은 데카르트적 회의의 대상이 된다. 데카르트 회의론의 목적에 관해서는 여러 가지 해석이 있다. 이 중 가장 저명한 것은 토대주의자들의 주장으로 데카르트의 회의론은 의심이 가능한 모든 믿음을 제외하는 것으로서 기본적인 신념만을 남기는 것을 목표로 한다는 것이다. 이러한 의심할 여지가 없는 기본 신념으로부터 데카르트는 다음 지식을 파생하려고 시도한다. 그는 지식을 상대적인 관점으로 바라보는 것이 아니라 절대적인 진리를 토대로 쌓아갔다. 이는 대륙철학의 합리주의를 축약시켜 보여주는 원형적이고 중요한 예시이다.

기법[편집]

데카르트적 회의는(4개의 과학적인 단계로 나눌 수 있다. 첫째, 사실이라고 아는 정보를 받아들이는 것. 둘째, 이 사실들을 더 작은 단위로 나누는 것. 셋째, 간단한 문제들을 먼저 해결하는 것. 넷째, 더 확장된 문제들의 완전한 목록을 만드는 것. ) 의심을 과대하게 하는 것이므로 의심의 경향성을 가진다고 한다. (데카르트의 기준으로의 지식은 단순히 합리적인 것 아닌 가능한 모든 의심을 넘어선 것을 말한다. ) 그의 성찰(1641)에서 데카르트는 의심할 수 없는 절대적인 진리로만 이루어진 믿음체계를 처음부터 끝까지 철저하게 만들기 위하여 자신의 모든 믿음의 진실 여부를 의심하기에 이르렀다.

데카르트의 방법[편집]

데카르트적 회의의 원조인 르네 데카르트는 모든 신념, 아이디어, 생각, 중요성을 의심에 두었다. 그는 어떠한 지식에 대한 그의 근거나 추리 또한 거짓일 수도 있다는 것을 보여주었다. 지식의 초기 상태인 감각적 경험은 잘못되었을 확률이 높기 때문에 의심되어야 한다. 예를 들어, 어느 사람이 보는 것은 환각일 수도 있다. 그가 보는 것이 환각이 될 수 없다는 것을 증명할 수 있는 것이 없다. 즉, 만약, 어떠한 신념이 논박될 수 있는 방법이 하나라도 존재한다면, 이의 진실 여부에 대한 근거가 불충분한 것이다. 이 것으로부터 데카르트는 꿈과 악마라는 두 가지 주장을 제안했다.

데카르트는 인간은 자신이 깨어있다는 것을 믿는 다는 것을 가정했을 때, 우리가 꿈을 꿀 때 믿기 어려운 와중에 현실 같을 경우가 있다는 것을 알고 있었다. 깨어있을 때의 경험과 꿈을 꿀 때의 경험을 구별할 수 있는 충분한 근거가 없다. 데카르트는 우리가 꿈이라는 생각들을 만들어낼 수 있는 세계에 산다는 것을 인정했다. 하지만, 성찰(1641)의 끝에 가서는 적어도 회상을 할 때에는 꿈과 현실을 구분할 수 있다고 결론을 내렸다.

데카르트는 우리가 경험하는 것이 악의적 천재에 의해 조정 당하고 있는 것일 수 있다고 생각했다. 이 천재는 똑똑하고 강하며 남을 잘 속인다. 데카르트는 그가 우리가 살고 있다고 생각하는 허울적인 세상을 만들었을 수도 있다고 생각했다.

성찰(1641)에서 데카르트는 한 사람이 미쳤었다면, 그 광기가 그 사람이 옳다고 생각했던 것이 자신의 정신이 자신을 속이는 것일 수도 있다고 생각하게 된다고 하였다. 그는 또한 우리가 올바른 판단을 내리는 것으로부터 막는 어떤 강력하고 교활한 악마가 존재할 수 도 있다고 했다.

데카르트는 그의 모든 감각들이 거짓말을 할 때, 한 사람의 감각이 그 사람을 쉽게 속일 수 있기 때문에 그 생각을 자신에게 거짓을 할 이유가 없는 강력한 존재가 심어두었으며 그의 강력한 존재에 대한 생각은 사실일 수 밖에 없다고 생각하였다.

코기토 에르고 숨[편집]

자신의 존재조차도 의심의 방법을 적용하여 의심하는 것이 ”Cogito ergo sum”(나는 생각한다, 고로 존재한다., 코기토 에르고 숨)이란 말을 탄생시켰다. 데카르트는 자신의 존재를 의심하려고 했지만, 존재하지 않는 다면 의심할 수 없기 때문에 그가 의심을 하고 있다는 사실이 그의 존재를 증명하는 것이라는 것을 깨달았다.

합리론[편집]

인식론에서 합리주의란 사실의 기준이 감각이 아닌 지적이고 연역적인 것이다. 이 방법을 강조하는 정도에 따라 서로 다른 관점의 합리주의자들이 있다. 추리력이 지식을 얻는 다른 방법들보다 우선적이라는 온건한 위치부터 추리가 지식을 얻는 유일한 방법이라는 극단적인 위치까지 존재한다. 근대 이전의 합리주의는 철학과 같은 것을 의미했다.

배경[편집]

계몽운동 이후로, 합리론은 데카르트, 라이프니츠, 스피노자에서와 같이 수학적인 방법을 철학에서 사용하기 시작한다. 합리주의는 영국에서 경험주의가 우세했던 것과는 달리 유럽의 대륙 쪽에서 우세했기 때문에 대륙 합리주의라고도 불린다. 합리주의는 경험주의와 자주 대조된다. 하지만, 어떤 사람이 합리주의를 믿으며 동시에 경험주의를 믿을 수 있다는 점만을 봐도 아주 넓게 보았을 때 이 두 관점은 서로를 완전히 배제하지 않는다는 것을 알 수 있다. 극단적인 경험주의자는 모든 생각이 외적인 감각이던 내적인 감정이던 경험을 통해 얻는다는 관점을 갖는다. 따라서 지식은 본질적으로 경험으로부터 유추되거나 경험을 통해 직접 얻는다는 입장이다. 경험주의와 합리주의에 있어서 논점이 되는 것은 인간의 지식의 근본과 우리가 알고 있다고 생각하는 것을 증명하는 적절한 방법이다. 합리주의의 몇 부류의 지지자들은 기하학의 자명된 이치와 같은 근복적이고 기초적인 원칙들로부터 나머지 모든 지식들을 연역적으로 유추할 수 있다고 주장한다. 이 관점을 가졌던 철학자들로는 스피노자와 라이프니츠를 들 수 있다. 이 둘은 데카르트에 의해 제기 되었던 인식론 상의 근본 원리에 대한 문제들을 해결하려고 시도하는 것으로 합리주의의 근본적인 접근의 발전을 가져왔다. 스피노자와 라이프니츠 둘 다 원칙적으로는 과학적 지식을 포함한 모든 지식이 추론만을 통해 얻을 수 있다고 주장했지만, 수학을 제외한 영역에서는 인간에게 실질적으로 불가능하다는 것을 관찰했다. 합리주의자와 경험주의자의 구별은 나중에 일어난 일로 그 시기의 철학자들은 알지 못했다. 그 구별 또한 애매하여 대표적인 세 합리주의자들은 경험주의에 있어서도 중요하게 평가된다. 또한, 많은 경험주의자들이 스피노자와 라이프니츠보다 데카르트의 방법론에 가까웠다.

합리주의와 데카르트[편집]

데카르트는 불변의 사실들에 대한 지식들만 추리를 통해서만 도달할 수 있다고 생각했다. 다른 지식들은 과학적 방법의 도움을 받아 경험을 필요로 한다고 생각했다. 그는 또한 꿈이 감각적 경험과 같이 생생하게 느껴지지만, 이러한 꿈들은 사람에게 지식을 제공할 수는 없다고 했다. 또한, 자각하고 있는 감각적 경험은 환각이 원인이 될 수도 있기 때문에 감각적 경험 자체가 의심의 여지가 있다고 했다. 그 결과로 데카르트는 사실을 찾기 위해서는 현실의 모든 믿음을 의심해야 한다는 것을 연역적으로 얻어내었다. 그는 이러한 믿음을 방법서설, 제1 철학에 관한 성찰과 철학원리에 실었다. 데카르트는 지적으로 인정되지 않은 것은 지식으로 분류하지 않는 방법을 통해 사실을 찾아내는 방법을 발전시켰다. 이러한 방법을 통해 얻어낸 사실들은 데카르트에 의하면 어떠한 감각적 경험을 필요로 하지 않았다. 추론을 통해 얻어낸 사실은 직관적으로 알 수 있는 작은 요소들로 나뉘어 연역적인 방법을 통해 현실에 대한 명백한 사실들에 도달할 것이다. 따라서 데카르트는 그의 방법의 결과로 추론은 지식을 결정짓는 유일한 방법이며 이 방법은 감각의 도움 없이 행해질 수 있다고 주장했다. 코기토 에르고 숨은 어떠한 경험의 간섭도 받지 않은 결론이다. 이는 데카르트에게 있어서 반박할 수 없는 논리로서 다른 모든 지식을 쌓을 수 있는 토대가 되었다.

이원론[편집]

“나는 생각한다, 그러므로 나는 존재한다.”(Cogito, ergo sum)라는 명제는 그의 형이상학의 제일원리인 동시에, 견실한 과학에 도달하기 위한 제일 원리였다. 데카르트는 기존의 사상에 반동적이었으며 과학에서 발견된 사실을 철학적인 세계관에 옮기려고 시도하였다. 그는 갈릴레오의 기하학적 물리학에 큰 영향을 받았으나, 데카르트가 보기에 그것은 엄밀성이 부족했다. 감각에 기초한 물질 세계의 개념과 좀더 엄격한 수학적인 물질세계의 개념을 구별하는 가운데, 데카르트는 후자가 더 객관적인 것이라는 입장을 취하였다. 그에게 있어서 물질 세계를 지각하는 감각적 경험은 주관적이며 자주 착각을 일으키고 외부세계와 동일한지 알 수 없기 때문에 회의의 대상이 되었다.

그의 목표는 주관을 넘어서 객관적 지식을 확보할 수 있는가에 있었다. 따라서 그가 취하는 입장은 감각적 경험이 아닌 이성관념으로, 이는 선험적으로 우리에게 주어지는 것이었다. 데카르트는 자신에게 주어진 선험적 관념에 따라, 실체를 정신적인 것과 물질적인 것 두 가지로 구분했다. 왜냐하면 정신과 육체는 명확하고 명료한 속성들의 전적으로 구별되는 두 조합을 통해 이해될 수 있기 때문이었다.

그에게 있어서 정신적인 실체의 본성은 사유하는 것(res cogiton)이며 물질적인 실체의 본성은 연장된 것(res extensa)였다. 먼저 정신은 연장적인 특징이 없고 불가분적이므로, 연장을 지니고 있는 물질과는 판명하게 구분된다. 데카르트는 육체 없이도 존재하는 나를 상상할 수 있다고 하면서, 정신을 물질과는 분리되어 생각할 수 있는 또 하나의 실체로 본 것이다. 이러한 정신은 좁은 의미에서는 순수한 지성(수학, 철학을 탐구하는)을 뜻하며 넓은 의미에서는 상상 작용, 감각 작용이 속한다. 감각 작용 신체에서 온 감각인 내부 감각과 외부사물로부터 비롯된 외부 감각으로 나뉜다. 내부감각은 다시 어디에서 오는지 위치를 알 수 있는 고통, 배고픔, 목마름과 같은 관념과 위치를 알 수 없는 분노, 슬픔과 같은 정념으로 나뉜다. 이 신체들의 내부감각은 정신을 속여 가짜의지를 생성해서 신체를 움직이게 한다. 그에게 있어 정신은 인간적인 것이 아니라 유한한 것이며, 제한 되어있지만 신과 동일한 유형의 능력을 지니고 있는 것이다. 이에 따라 정신적인지 판단하는 기준은 신이었으며, 이런 배경으로 인해 순수하게 지적인 능력인 상상력이나 감각 지각과 같이 육체를 전제로 하는 능력과 구분된다고 생각하였다.

한편 데카르트에게 있어서 물질(육체)은 연장을 가지고 있으며, 기하학적 공간에 위치하기 때문에, 섞여있거나 겹치지 않는다. 또한 기하학의 원리에 따라 무한 분할이 가능하며 이러한 모든 물체의 위치와 공간은 기하학적 공간에서 좌표화 가능한 것이다. 데카르트의 이러한 공간 개념에 있어서 빈 공간은 존재하지 않으며, 항상 물질에 의해 점유되어 있는 것으로서 운동은 연쇄적으로 각 물질의 위치가 바뀌는 것을 의미하는 것이다.

데카르트에게 있어 관념들 자체는 사물의 본성이 아니라 그와 유사한 것으로 각 관념들은 물체를 특수한 방식으로 그려낸다. 또한 정신과 육체는 섞여있는 것이다. 과거 플라톤의 정신과 신체는 선원과 배의 관계로 한쪽이 다른 한쪽을 지배하는 것이었으나, 데카르트는 이 둘이 밀접하게 연관되어 있다고 한다. 이에 대해 데카르트는 송과선이라는 솔방울 모양의 샘을 통해 설명하려 한다. 육체가 신경선으로 동물정기라는 기체화된 혈액을 자극하면 인과적으로 감각적 내용이 송과선을 통해 정신에게 전달된다는 것이다. 데카르트는 이러한 설명에 대해 기계적인 방식으로 ‘자연에 의해 확립되었다’라는 주장을 한다.

데카르트 사상과의 대립[편집]

아이작 뉴턴[편집]

과학혁명 이전의 자연관은 지금과는 완전히 달랐다. 자석들은 왜 서로 잡아당기거나 밀어낼까? 상처에 약을 바르면 왜 나을까? 이런 질문에 대해서 르네상스 자연주의에서는 자연을 살아있는 신비한 생명체로 파악하며, 자석의 N극과 S극이 서로 잡아당기는 이유는 서로가 공감을 하기 때문이고, N극과 N극이 밀치는 이유는 서로 반감을 가지고 있기 때문이라고 설명했다. 식물이 성장하고, 동물이 스스로 자각해서 움직이는 모든 운동의 원리를 영혼으로 보았다. 이렇게 자연을 마치 생명과 감정이 있는 인간처럼 여기는 르네상스 자연주의는 신비주의적인 성격을 띠게 되었고, 자연에 대한 합리적인 설명을 추구할 동기로 부여하지 못했다. 하지만 근대 과학은 자연에서 신비로움을 제거해 버렸다. 자연은 객관적 실체로 이루어져 있고, 수학적 법칙에 의해서 설명할 수 있으며, 자연에서 일어나는 모든 운동은 외적인 요인에 의해서 이루어진다는 신념을 가져다 주었다. 이런 근대 과학의 출발점이 된 것이 바로 데카르트와 아이작 뉴턴이다.

데카르트는 "기계적 철학(mechanical philosophy)"을 제시하며, 우리가 세상을 보는 방식을 새롭게 규정했다. 기계적 철학은 자연은 눈에 보이지 않는 미세한 물질로 이루어져 있으며, 자연 현상이란 이런 물질들의 운동에 의해서 일어난다고 전제하고, 각종 자연 현상들을 미세한 물질들의 직선 운동과 충돌로 설명했다. 앞에서 르네상스 자연주의자들이 자석을 공감, 반감을 이용해서 설명했던 것에 비해서, 데카르트의 기계적 철학에서는 입자와운동이라는 개념을 이용해서 설명하고 있다. 즉, 자석에는 눈에 보이지 않는 아주 작은 구멍들이 있고, 자석 주변에는 눈에 보이지 않는 작은 나사들이 배열되어 있어서 자석의 구멍을 통해서 작은 나사들이 통과하는데, 나사들의 운동 방향에 따라서 자석은 서로 끌리기도 하고, 서로 밀어내기도 한다는 것이다. 르네상스 자연주의에서 자석은 외부에서 특별히 힘이 작용하지 않아도 스스로 움직이는 매우 신비로운 존재로 여겨졌지만, 기계적 철학의 눈으로 본 자석은 신비로움을 잃었다. 이렇게 데카르트는 자연을 합리적이고 명쾌하게 이해가 가능한 대상으로 만들었다.

기계적 철학에서는 생명체와 비생명체의 구분조차 불필요했다. 데카르트에게 자연은 단지 기계에 불과했으며, 그 자체의 목적이나 생명은 존재하지 않았다. 그는 이렇게 자연에서 영혼을 제거시켜서, 중세적 자연관을 밀어내고 기계적 세계관을 정당화했다. 이로써 자연은 기계적 법칙에 따라 움직이며, 자연계의 만물은 물체의 위치와 운동으로 설명 가능한 것이 되어버렸다. 이렇게 데카르트는 17세기 과학혁명의 기본 구조를 만들어냈지만, "자연은 정확한 수학적 법칙에 의해 지배되는 완전한 기계"라는 그의 생각은 일생동안 하나의 가설로 남아있어야 했다.

데카르트의 꿈을 실현시키고, 과학혁명을 완성한 사람은 아이작 뉴턴이었다. 데카르트의 기계적 철학에서 "운동"이라는 개념을 이어받아, 뉴턴도 자연 현상의 기본을 운동으로 이해했다. 하지만 운동을 표현하는 방식에서는 데카르트보다 한 걸음 더 나아가서, 입자의 운동에 수학적 성격을 합친 "힘"이라는 개념을 가져와, 운동을 정량적으로 분석했다. 다시 말해서 "힘"을 운동의 원인으로 설정하여, 힘의 수학적인 표현을 찾아내고, 거기서부터 가속도, 속도, 물체의 움직이는 궤적 등을 계산하는 역학의 방법을 정식화했다.

뉴턴은 결국 데카르트를 뛰어넘지만, 가장 근본적인 부분에서는 데카르트와 공유하는 부분이 많았다. 복잡한 자연을 단순하게 분해해서 이해하는 방식이나, 운동에서 자연 현상의 근원을 찾고, 그 운동을 수학적인 언어로 풀어내려고 했던 점 등은 두 사람 모두에게서 발견되는 경향이다.

17세기 말에서 18세기까지 "프랑스의 데카르트와 영국의 뉴턴 중 누가 옳았는가" 하는 문제가 양국 과학자들의 관심사로 떠오르면서 두 사람의 공통점보다 차이점이 더 많이 부각되어 왔지만, 사실 두 사람은 차이점보다 공유하는 것이 더 많았던 사람들이다. 어떻게 보면, 두 사람을 그렇게 항목별로 비교할 수 있다는 점 자체가 역설적으로 두 사람이 공통의 관심사를 가지고 있었다는 것을 반증하는 것일 수도 있다.

우리에게 있어서 데카르트와 뉴턴의 가장 큰 공통점은 우리가 자연 세계를 바라보는 방식을 새롭게 규정했다는 점에 있다. 20세기 초에 양자역학과 상대성이론의 등장으로 위기를 맞는 듯했지만, 여전히 우리의 일상 세계는 데카르트와 뉴턴이 확립해 놓은 고전역학의 법칙에 따라서 움직이고 있다.

스피노자[편집]

스피노자는 실체를 다음과 같이 정의한다. "실체란 자신 안에 있으며, 자신에 의하여 생각되는 것이라고 이해한다. 즉, 실체는 그것의 개념을 형성하기 위해서 다른 것의 개념을 필요로 하지 않는 것이다. "자신 안에 있다는 것"은 그 자체로 존재한다는 뜻이고, "그 자체로 존재한다는 것"은 다른 것에 의존하지 않고 자립적으로 존재함을 뜻하고, "자기 자신에 의해서 생각된다는 것"은 그 개념을 형성하기 위해서 다른 어떤 것을 필요로 하지 않음을 뜻한다. 그러므로 스피노자는 실체를 다른 것에 의존하지 않는 독립적 존재로 파악하고 있음을 알 수 있다.

데카르트는 그 정의를 실체로 적용할 때,의미를 악화시켜서 자신이 내린 정의에 충실히 따르지 않았다. 그는 실체란 "존재하기 위해서 신의 도움만을 필요로 하는 것들"이라고도 정의한다. 이는 실체 개념을 창조물에까지 확대시킨 것이다. 반면 스피노자는 자신이 내린 실체 개념을 엄격히 적용하였다. 스피노자에 따르면, 실체는 자립적 존재이기 때문에 "유한 실체"라는 말은 불합리한 개념이며, 신만이 실체라고 주장한다. "신 이외에는 어떠한 실체도 존재할 수 없으며, 또한 파악될 수도 없다"고 한 스피노자의 정리에서 잘 드러난다.

신이 어떤 존재이며, 어떤 방식으로 세계에 개입하는지에 대해서도 두 사상가는 커다란 입장 차이를 보인다. 이신론을 주장하는 데카르트의 신은 인격을 소유한 존재이다. 그러므로 세계를 자신의 의지에 따라 창조, 소멸, 심지어는 개입할 수도 있다. 반면 스피노자는 신을 그런 초월적 존재로 보지 않는다. 신의 의지에 의한 "기적"같은 것은 신의 작동 방식을 법칙으로 이해하고자 한 스피노자에게는 비합리적인 것이다.

종교적인 믿음[편집]

르네 데카르트의 종교적 믿음은 학계에서 엄밀히 논쟁되어 왔다. 그는 <제1철학에 관한 성찰>의 목적들 중 하나가 기독교 신앙을 옹호하기 위한 것이라고 주장하면서 독실한 로마 가톨릭 신자가 되는 것을 주장했다. 하지만 그의 시대에서 데카르트는 이원론 또는 무신론을 믿은 것으로 비난받았다.

동시대의 블레즈 파스칼은 "그의 철학에서 데카르트를 용서할 수 없다. 데카르트는 신 없이 지내기 위해서 최선을 다했다. 하지만 데카르트는 신에게 손가락 움직임 하나만으로 세계를 확립하라고 재촉하는 것을 피할 수 없었지만, 그 후에 그는 신을 더 이상 필요로 하지 않았다."

스티븐 고크로져의 데카르트 전기는 그가 죽는 날까지 진리를 발견하기 위한 단호하고, 열정적인 열망과 함께 로마 가톨릭 교회에 깊은 종교적 믿음을 가졌다고 저술한다. 데카르트가 스웨덴에서 죽은 후, 크리스티나 여왕은 스웨덴의 법이 신교도 지도자를 요구했기 때문에, 로마 가톨릭 교회로 바꾸기 위해서 그녀는 왕위에서 물러났다. 로마 가톨릭 교회에 대해서 그녀가 장기적으로 접촉한 사람은 개인 지도 교사인 데카르트뿐이었다.

평가와 비판[편집]

엥겔스: "데카르트의 변수는 수학의 전환점이 되었다. 변수가 생긴 뒤로, 운동과 변증법이 수학의 영역으로 들어올 수 있었다."

버터필드: "방법서설은 우리 문명의 역사상 가장 훌륭한 저작이다."

묘비명: "데카르트, 유럽 르네상스 이후 인류를 위해서 처음으로 이성의 권리를 쟁취하고 확보한 사람이다."

주요 저서[편집]

- 데카르트 전집: Oeuvres de Descartes, 편집 Ch. Adam et P. Tannery, 11판, 1982-1991 Paris.

- 《음악개론》: Compendium Musicae, 1618년

- 《정신지도의 법칙》: Regulae ad directionem ingenii(Rules for the Direction of the Mind), 1626-1628년

- 《인간, 태아발생론》: L'Homme(Man), 1630-1633년, 1662년 출판

- 《천체론》: Le Monde(The World), 1630-1633년, 1664년 출판

- 《방법서설》: Discours de la méthode(Discourse on the Method), 1637년 문예출판사 1997, ISBN 89-310-0327-7

- 《기하학》: La Géométrie(Geometry), 1637년

- 《성찰》: Meditationes de prima philosophia, 1641년 양진호, 옮김, 책세상출판사 2011, ISBN 89-7013-790-4

- 《성찰》: Meditationes de prima philosophia, 1641년 이현복 옮김, 문예출판사 1997, ISBN 89-310-0326-9

- 《철학의 원리》: Principia philosophiae, 1644년 원석영 옮김, 아카넷 2002, ISBN 89-89103-83-5

- 《프로그램에 대한 주석》: Notae in programma(Comments on a Certain Broadsheet), 1647년

- 《인체의 구조에 관하여》: The Description of the Human Body, 1647년

- 《데카르트의 철학원리》: Responsiones Renati Des Cartes(Conversation with Burman), 1648년

- 《정념론》: Les passions de l'âme(Passions of the Soul), 1649년

- 《음악에 관한 소고》: Musicae Compendium(Instruction in Music), 1656년, 사후 출판

- 《조응》: Correspondance, 1657년, 클라우데 클레르슬리에(Claude Clerselier)에 의해 출판

같이 보기[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ Russell Shorto. Descartes' Bones. (Doubleday, 2008) p. 218; see also The Louvre, Atlas Database, http://cartelen.louvre.fr

- ↑ Marenbon, John (2007년). Medieval Philosophy: an historical and philosophical introduction. Routledge. 174쪽. ISBN 978-0-415-28113-3

- ↑ Étienne Gilson argued in La Liberté chez Descartes et la Théologie (Alcan, 1913, pp. 132–47) that Duns Scotus was not the source of Descartes'Voluntarism. Although there exist doctrinal differences between Descartes and Scotus "it is still possible to view Descartes as borrowing from a Scotist Voluntarist tradition" (see: John Schuster, Descartes-Agonistes: Physcio-mathematics, Method & Corpuscular-Mechanism 1618-33, Springer, 2012, p. 363, fn. 26).

- ↑ "Cartesianism (philosophy): Contemporary influences" in Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ 양, 진호 (2011년). 《성찰: 해제 르네 데카르트를 찾아서- 성찰의 시대, 시대의 성찰》. 책세상. 150쪽. ISBN ISBN 978-89-7013-790-2

|isbn=값 확인 필요 (도움말). - ↑ 《글로벌 세계대백과사전》

참고 및 관련 문헌[편집]

- 이보경, 데카르트의 형이상학적 자연학, 서울대학교 석사 학위 논문, 2001

- 이성근, 데카르트의 형이상학적 회의에 대한 연구: 『성찰』을 중심으로, 서울대학교 석사 학위 논문, 2007

- 김현선, 데카르트의 "사유하는 정신": 보편학으로서 철학의 과제와 관련하여, 이화여자대학교 석사 학위 논문, 1995

- Domski, Mary, "Descartes' Mathematics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta(ed.), URL=<http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/descartes-mathematics/>

- 안광복, 철학, 역사를 만나다, 웅진지식하우스

- 르네 데카르트, 방법서설(정신 지도를 위한 규칙들), 이현복 역, 문예출판사 1997, ISBN 89-310-0327-7

- 르네 데카르트, 성찰(자연의 빛에 의한 진리 탐구, 프로그램에 대한 주석), 이현복 역, 문예출판사 1997, ISBN 89-310-0326-9

- 르네 데카르트, 성찰: 해제-르네 데카르트를 찾아서: 성찰의 시대, 시대의 성찰, 양진호 역, 해제: 양진호, 책세상 2011, ISBN 978-89-7013-790-2

- 르네 데카르트, 철학의 원리, 원석영 역, 아카넷 2002, ISBN 89-89103-83-5

바깥 고리[편집]

|

이 문서는 2015년 3월 14일 (토) 15:17에 마지막으로 바뀌었습니다.

편집모드 => https://ko.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%EB%A5%B4%EB%84%A4_%EB%8D%B0%EC%B9%B4%EB%A5%B4%ED%8A%B8&action=edit

>>>

https://ko.wikiquote.org/wiki/르네_데카르트

르네 데카르트

르네 데카르트(프랑스어: René Descartes, 라틴어: Renatus Cartesius, 1596년 3월 31일 - 1650년 2월 11일) 프랑스의 대표적 근세철학자이다.

출처 있음[편집]

- 나는 생각한다. 고로 나는 존재한다.[1]

- 착오가 흔히 생기게 되는 것은 자기가 판단하려는 사물에 대하여 아주 정확한 지식이 없으면서도 경솔하게 판단을 하기 때문이다.

- 어떤 사실을 내가 참이라고 확신하기 전에는 그것을 절대 진리로 받아들이지 말자.[2]

- 내가 다루고자하는 문제의 쉬운 해결을 위해서 될 수 있는대로 그리고 필요한만큼 나누어 살펴보자.[3]

- 사유는 가장 간단하고 쉽게 한 눈에 살펴볼 수 있는 것에서 시작하자.[4]

- 자세히 차례를 정하고 개관을 세우자. [5]

주석[편집]

이 문서는 2014년 4월 19일 (토) 15:35에 마지막으로 바뀌었습니다.

>>>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

René Descartes

| René Descartes | |

|---|---|

Portrait after Frans Hals, 1648[1] | |

| Born | 31 March 1596 La Haye en Touraine,Kingdom of France |

| Died | 11 February 1650 (aged 53) Stockholm, Swedish Empire |

| Nationality | French |

| Religion | Catholic[2] |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Cartesianism, rationalism,foundationalism, founder ofCartesianism |

Main interests | metaphysics, epistemology,mathematics |

Notable ideas | Cogito ergo sum, method of doubt, method of normals,Cartesian coordinate system,Cartesian dualism, ontological argument for the existence of God, mathesis universalis; folium of Descartes |

| Signature | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| René Descartes |

|---|

| Cartesianism · Rationalism Foundationalism Doubt and certainty Dream argument Cogito ergo sum Trademark argument Causal adequacy principle Mind–body dichotomy Analytic geometry Coordinate system Cartesian circle · Folium Rule of signs · Cartesian diver Balloonist theory Wax argument Res cogitans · Res extensa |

| Works |

| The World Discourse on the Method La Géométrie Meditations on First Philosophy Principles of Philosophy Passions of the Soul |

| People |

| Christina, Queen of Sweden Baruch Spinoza Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Francine Descartes |

René Descartes (/ˈdeɪˌkɑrt/;[5] French: [ʁəne dekaʁt]; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; adjectival form: "Cartesian";[6] 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, mathematicianand writer who spent most of his life in the Dutch Republic.

He has been dubbed the father of modern philosophy, and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings,[7][8] which are studied closely to this day. In particular, his Meditations on First Philosophy continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes' influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system — allowing reference to a point in space as a set of numbers, and allowing algebraic equations to be expressed as geometric shapes in a two-dimensional coordinate system (and conversely, shapes to be described as equations) — was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the scientific revolution and has been described as an example of genius.

Descartes refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers, and refused to trust his own senses. He frequently set his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, a treatise on the early modern version of what are now commonly calledemotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic "as if no one had written on these matters before". Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in lateAristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differs from the schools on two major points: First, he rejects the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejects any appeal to final ends—divine or natural—in explaining natural phenomena.[9] In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God's act of creation.

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting ofHobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza and Descartes were all well versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

His best known philosophical statement is "Cogito ergo sum" (French: Je pense, donc je suis; I think, therefore I am), found in part IV of Discourse on the Method (1637 – written in French but with inclusion of "Cogito ergo sum") and §7 of part I of Principles of Philosophy (1644 – written in Latin).

Contents

[hide]Life[edit]

Early life[edit]

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine (now Descartes), Indre-et-Loire, France, on March 31, 1596. When he was one year old, his mother Jeanne Brochard died. His father Joachim was a member of the Parlement of Brittany at Rennes.[10] René lived with his grandmother and with his great-uncle. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots.[11] In 1607, late because of his fragile health, he entered the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche[12] where he was introduced to mathematics and physics, including Galileo's work.[13] After graduation in 1614, he studied two years at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat andLicence in law, in accordance with his father's wishes that he should become a lawyer.[14] From there he moved to Paris.

In his book, Discourse On The Method, he says "I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way so as to derive some profit from it."

Given his ambition to become a professional military officer, in 1618, Descartes joined the Dutch States Army in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau, and undertook a formal study of military engineering, as established by Simon Stevin. Descartes therefore received much encouragement in Breda to advance his knowledge of mathematics.[15] In this way he became acquainted with Isaac Beeckman, principal of a Dordrecht school, for whom he wrote the Compendium of Music (written 1618, published 1650). Together they worked on free fall, catenary, conic section and Fluid statics. Both believed that it was necessary to create a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics.[16]While in the service of the Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, Descartes visited the labs of Tycho Brahe in Prague and Johannes Kepler in Regensburg.

Visions[edit]

According to Adrien Baillet, on the night of 10–11 November 1619 (St. Martin's Day), while stationed in Neuburg an der Donau, Descartes shut himself in a room with an "oven" (probably a Kachelofen or masonry heater) to escape the cold. While within, he had three visions and believed that a divine spirit revealed to him a new philosophy.[17] Upon exiting he had formulated analytical geometry and the idea of applying the mathematical method to philosophy. He concluded from these visions that the pursuit of science would prove to be, for him, the pursuit of true wisdom and a central part of his life's work.[18][19] Descartes also saw very clearly that all truths were linked with one another, so that finding a fundamental truth and proceeding with logic would open the way to all science. This basic truth, Descartes found quite soon: his famous "I think therefore I am".[16]

France[edit]

In 1620 Descartes left the army. He visited Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, then visited various countries before returning to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris. It was there that he composed his first essay on method: Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind).[16] He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property to invest in bonds, which provided a comfortable income for the rest of his life.[citation needed] Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627.[citation needed] In the fall of the same year, in the residence of the papal nuncio Guidi di Bagno, where he came with Mersenne and many other scholars to listen to a lecture given by the alchemist Monsieur de Chandoux on the principles of a supposed new philosophy.[20] Cardinal Bérulle urged him to write an exposition of his own new philosophy.[citation needed]

Netherlands[edit]

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628. In April 1629 he joined the University of Franeker, studying under Metius, living either with a Catholic family, or renting the Sjaerdemaslot, where he invited in vain a French cook and an optician.[citation needed] The next year, under the name "Poitevin", he enrolled at the Leiden University to study mathematics with Jacob Golius, who confronted him withPappus's hexagon theorem, and astronomy with Martin Hortensius.[21] In October 1630 he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, who was born in 1635 in Deventer, at which time Descartes taught at the Utrecht University. Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes was not devoid of passions but rather defended them; he wept upon her death in 1640.[22] "Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man." Russell Shorto postulated that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes' work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.[23]

Despite frequent moves[24] he wrote all his major work during his 20+ years in the Netherlands, where he managed to revolutionize mathematics and philosophy.[25] In 1633, Galileo was condemned by theCatholic Church, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish Treatise on the World, his work of the previous four years. Nevertheless, in 1637 he published part of this work in three essays: Les Météores(The Meteors), La Dioptrique (Dioptrics) and La Géométrie (Geometry), preceded by an introduction, his famous Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method), also meant for women. In it Descartes lays out four rules of thought, meant to ensure that our knowledge rests upon a firm foundation.

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641 he published a metaphysics work, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed, in 1644, by Principia Philosophiæ (Principles of Philosophy), a kind of synthesis of the Meditations and the Discourse. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a long correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, devoted mainly to moral and psychological subjects. Connected with this correspondence, in 1649 he published Les Passions de l'âme (Passions of the Soul), that he dedicated to the Princess. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the Louis XIV, though it was never paid.[26]

A French translation of Principia Philosophiæ, prepared by Abbot Claude Picot, was published in 1647. This edition Descartes dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. In the preface Descartes praised true philosophy as a means to attain wisdom. He identifies four ordinary sources to reach wisdom, and finally says that there is a fifth, better and more secure, consisting in the search for first causes.[27]

Sweden[edit]

Queen Christina of Sweden invited Descartes to her court in 1649 to organize a new scientific academy and tutor her in his ideas about love. She was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish the "Passions of the Soul", a work based on his correspondence with Princess Elisabeth.[28]

He was a guest at the house of Pierre Chanut, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Tre Kronor in Stockholm. There, Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian barometer, a tube with mercury. Challenging Blaise Pascal, Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure could be used in forecasting the weather.[29][30]

Death[edit]

Descartes apparently started giving lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week, at 5 a.m, in her cold and draughty castle. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his mechanical philosophy, he did not appreciate her interest in Ancient Greek. By 15 January 1650, Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February he caught a cold which quickly turned into a serious respiratory infection, and he died on 11 February. The cause of death waspneumonia according to Chanut, but peripneumonia according to the doctor Van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him.[31] (The winter seems to have been mild,[32] except for the second half of January) which was harsh as described by Descartes himself. "This remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather."[28]

In 1991 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Van Wullen, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.[33] Descartes might have been assassinated[34][35] as he asked the doctor for an emetic: wine mixed with tobacco[36] and seems to have died without saying a word. However, Tore Frängsmyr, historian from Uppsala University, believes this theory is merely an attempt at attention getting on the part of the author.[35]

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard used mainly for orphans in Adolf Fredriks kyrka in Stockholm. His manuscripts came into the possession of Claude Clerselier, Chanut's brother-in-law, and "a devout Catholic who has begun the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding and publishing his letters selectively."[37] In 1663, the Pope placed his works on theIndex of Prohibited Books. In 1666 his remains were taken to France and buried in the Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. In 1671 Louis XIV prohibited all the lectures in Cartesianism. Although the National Convention in 1792 had planned to transfer his remains to the Panthéon, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819, missing a finger and the skull.[38]

Religious beliefs[edit]

The religious beliefs of René Descartes have been rigorously debated within scholarly circles. He claimed to be a devout Catholic, saying that one of the purposes of the Meditations was to defend the Christian faith, although his reasoning for being Catholic could be because he "preferred to avoid all collision with ecclesiastical authority."[2] However, in his own era, Descartes was accused of harboring secret deist oratheist beliefs. His contemporary Blaise Pascal said that "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God."[39]Stephen Gaukroger's biography of Descartes reports that "he had a deep religious faith as a Catholic, which he retained to his dying day, along with a resolute, passionate desire to discover the truth."[40]The debate continues whether Descartes was a Catholic/Christian apologist, or a deist/atheist concealed behind pious sentiments who placed the world on a mechanistic framework, within which only man could freely move due to the grace of will granted by God.[26]

Philosophical work[edit]

Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences.[41] For him the philosophy was a thinking system that embodied all knowledge, and expressed it in this way:[42]

| “ | Thus, all Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principals, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences, is the last degree of wisdom. | ” |

In his Discourse on the Method, he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as methodological skepticism: he rejects any ideas that can be doubted, and then reestablishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge.[43]

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: thought exists. Thought cannot be separated from me, therefore, I exist (Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy). Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum (English: "I think, therefore I am"). Therefore, Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, therefore the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. "The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist."[44]

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines "thought" (cogitatio) as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it". Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious.[45]

To further demonstrate the limitations of these senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as theWax Argument. He considers a piece of wax; his senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. When he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: it is still the same piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Therefore, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he should put aside the senses. He must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

| “ | And so something that I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgment which is in my mind. | ” |

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and instead admitting only deduction as a method. In the third and fifth Meditation, he offers an ontological proof of a benevolent God (through both the ontological argument and trademark argument). Because God is benevolent, he can have some faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, he finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. In terms of epistemology therefore, he can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge. He, nevertheless, was very much aware that experimentation was necessary in order to verify and validate theories.[42]

Descartes also wrote a response to External world scepticism. He argues that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, and are not willed by him. They are external to his senses, and according to Descartes, this is evidence of the existence of something outside of his mind, and thus, an external world. Descartes goes on to show that the things in the external world are material by arguing that God would not deceive him as to the ideas that are being transmitted, and that God has given him the "propensity" to believe that such ideas are caused by material things. He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams, and that one's mind cannot have been "hijacked" by an evil demon placing an illusory external world before one's senses.

Dualism[edit]

Descartes in his Passions of the Soul and The Description of the Human Body suggested that the body works like a machine, that it has material properties. The mind (or soul), on the other hand, was described as a nonmaterial and does not follow the laws of nature. Descartes argued that the mind interacts with the body at the pineal gland. This form of dualism or duality proposes that the mind controls the body, but that the body can also influence the otherwise rational mind, such as when people act out of passion. Most of the previous accounts of the relationship between mind and body had been uni-directional.